by S.M. Ikram

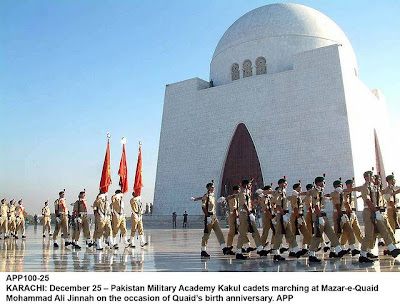

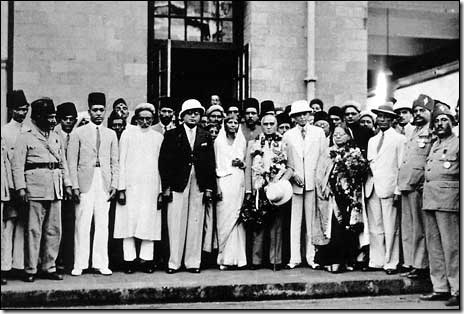

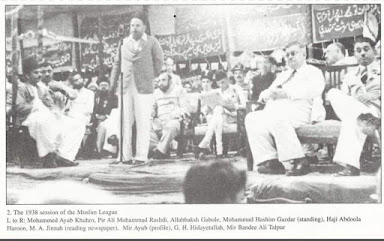

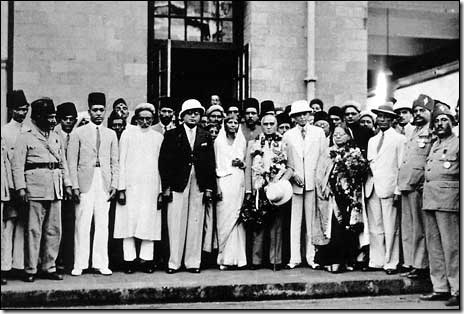

On the occasion of the All India Muslim League session, 1936

On the occasion of the All India Muslim League session, 1936

Jinnah was not invited to the later sessions of the Round Table Conference, but he was now residing in England, and had opportunities of meeting the delegates from India. An important contact, which he effectively renewed during this period was with Sir Muhammad Iqbal, who had come as a delegate to the Round Table Conference. Jinnah was the principal speaker at a reception given in honour of the poet by Iqbal Literary Association and thereafter invited him to lunch at his house. Thus began a series of meetings which were to leave a mark on the course of India’s history. Jinnah was not now a delegate to the Round Table Conference, but during the first session, which he attended, he had criticised to conception of the central federation, which other delegates had supported enthusiastically. His objections were partly from the nationalist anglet (sic) – the inclusion of the autocratic princes at the centre would “water down democracy” – and partly from the Muslim point of view – a strong centre would nullify the provincial autonomy which the Muslims valued so much. Iqbal, on the other hand, had a few years before, held out his plan for a Muslim bloc in the North-West. This did not receive much consideration at the Round Table Conference, but the separation of Sind, and grant of full reforms to the North-West Frontier Province were bound to pave the way for its fulfillment. This plan, the poet discussed at length with Jinnah, and gradually convinced him that in this lay the only hope for a contented, peaceful India in general and for the bulk of Indian Muslims in particular.

Iqbal had got Jinnah seriously interested in what came to be known as the “Pakistan Scheme” but even then he did not return to India to take it up. He was biding his time, and all the time, most unhappy. During the course of a brief visit to Oxford in 1932, he said to the present writer, with great anguish of soul, “but what is to be done? The Hindus are short-sighted and I think, incorrigible. The Muslim camp is full of those spineless people who, whatever they may say to me, will consult the Deputy Commissioner about what they should do! Where is, between these two groups, any place for a man like me?”

Iqbal had got Jinnah seriously interested in what came to be known as the “Pakistan Scheme” but even then he did not return to India to take it up. He was biding his time, and all the time, most unhappy. During the course of a brief visit to Oxford in 1932, he said to the present writer, with great anguish of soul, “but what is to be done? The Hindus are short-sighted and I think, incorrigible. The Muslim camp is full of those spineless people who, whatever they may say to me, will consult the Deputy Commissioner about what they should do! Where is, between these two groups, any place for a man like me?”

Meanwhile he was getting reports from India that Indian Muslims were a flock of sheep without a shepherd. The Aga Khan’s leadership was ineffective, as he wanted the palm without the dust, and could not give up the health resorts of France and Switzerland. Maulana Muhammad Ali was dead. So was Sir Muhammad Shafi, and even if he had been alive, he was too closely associated with a pro-British policy to inspire general enthusiasm. The League and the Muslim Conference had become the plaything of petty leaders who would not resign office, even after a vote of no-confidence! And, of course, they had no organization in the provinces, and no influence with the masses.

It was in these circumstances that certain well-wishers of the Muslims turned towards Jinnah. They requested him to return to India, and once again lead to army, which was first becoming a rabble. Iqbal joined in these appeals. Jinnah relented, but even now he would only visit India for a few months and return to England again. In 1934, however, he was elected the permanent president of the All-India Muslim League, and finally returned to India in October, 1935.

Back in India, Jinnah began to reorganize the All-India Muslim League. Its annual session was held at Bombay in April 1936, under the presidentship of Sir Wazir Hasan, and its constitution was revised to make it more democratic and living organization. Steps were also taken, for the first time, to set up a machinery for contesting elections on behalf of the Muslim League. A central election board with provincial elections under the Government of India Act of 1935. Jinnah toured the country to convass (sic) support for the League candidates, but his efforts were only partially successful. In the Punjab, he had the constant support of Iqbal, but could not come to an agreement with Sir Fazl-i-Hussain, the Unionist leader and League fared very badly in that ‘key’ province. Experience in Bengal was similar. In the elections, the League was actively assisted by the Jamiat-ul-Ulama, and had generally the goodwill of the Congress, which had been receiving support for Jinnah’s Independent Party in the Central legislative Assembly, but it failed to make much headway against firmly entrenched provincial parities.

The Rallying-Post

The provincial elections of 1937 produced many surprises. The League had not come out with flying colours. The Congress, on the other hand, achieved a success, which neither its supporters nor its opponents had anticipated. Most provincial Governors and British officials expected at the provincial election a repetition of the previous elections to the Central Legislature, when Congress had won about 50 per cent of the Hindu seats. They looked to the provincial parites, which they had encouraged in various areas – the Unionists in Punjab, the Justice Party in Madras, the Zamindars in the Nationalist Party in U.P., the Marathas in Bombay – and were sure that although the Congress may be the largest single party, it would have to depend on others to form ministries. Here they were to be completely disillusioned. The organizing ability of Sardar Vallabhbhi Patel, who had succeeded Dr. Ansari as the Chairman of the Parliamentary Board, the army of the workers, which the Congress had built up during the previous twenty years, the magic name of Mahatma, and the whirlwind tours of the president, Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru, completely upset the official calculations. The Congress triumphed in all the Hindu provinces and even in the North-West Frontier!

There is no doubt that this unexpected success went to the head of the Congress leaders. Before and even during the elections, they were friendly to the Muslim League. Now they were cold and distant. Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru declared at Calcutta that there were only two parties in the country – the British and the Congress. The League had fared so badly at the elections that it was not necessary to acknowledge its existence. To this attitude of high disdain, two other factors contributed. The Congress president was surrounded by certain left wing – almost de-Muslimised – Muslims, who later left even the Congress fold for the Communists’ ranks. They urged on Nehru, that it was “medieval” to recognize political parties based on religions, and the Congress had only to organize a vigorous Muslim Mass Contact Movement to achieve the same success amongst the Muslims, which it had gained among the Hindus. Nehru was carried away by these visions, and an open breach occurred between the Congress and the League. While in the original elections, the Congress had supported the League in U.P. now it set up a candidate to oppose the Muslim League in Bhraich constituency of U.P. which had returned a Leaguer, who died shortly after the elections.

The personality of the chairman of the Congress parliamentary board was another factor, which drove the Congress away from the League. Sardar Patel was a great organizer but for a man of his ability and importance, he was amazingly ill-informed about the background of Muslim politics, and even otherwise perhaps freedom from communalism was not one of his many gifts. He was at this time at the summit of the Congress parliamentary board, bossed over all government in the Congress provinces. He had to decide the question of Muslim representation in provincial government, and he dealt with the problem in his usual firm and unimaginative way. If he had faced the question in a spirit of statesmanship, he could have seen that Sir Sikandar Hayat and other Muslim premiers had already tackled the corresponding Hindu problem in the Muslim provinces, in a manner which could be a very safe guide to the Congress. Sir Sikandar Hayat’s party was in absolute majority in the Punjab Assembly, but he offered the Hindu seat in the Government to the Hindu Mahasabha, and although Raja Narendara Nath, the president of the Hindu Party, was unable to accept it owing to old age, his nominee, Sir Manohar Lal was appointed a minister. There was really no other way to give honest, real, representation to the minorities. If a minister had to be taken not on account of affiliation to the party, or any other personal claim, but to represent the minorities, it was obvious that he should be their genuine representative and not a stooge of the party in power. This the iron-willed Sardar would not – or could not – grasp. Under the constitution, representation had to be given to the minorities. So he was prepared to have Muslim ministers even from the Muslim League – but then, they must resign from the League, sign the Congress pledge, and abide by its discipline. In other words, the minority representatives were not to represent the minorities but the Congress! In imposing his iron discipline, the Sardar had some initial difficulties. The Muslim League had not done well in predominantly Muslim areas, but it had won the vast majority of seats in the Congress provinces. In some of these – like Bombay – not a single Muslim had been returned on the Congress ticket. So what was to be done about the representation of the Muslims in the Governments of these provinces? The problem was somewhat complicated but the efficient, resourceful Sardar was not going to be baffled by these difficulties. He offered the ministry to any Tom, Dick or Harry amongst the Muslim members who was prepared to sign the Congress pledge and so the farce of Muslim representation was complete.

The procedure adopted was, of course, a negation of the constitutional safeguards for the Muslims, but it was also less than fair to the Muslim League. Before the elections the Congress and Jinnah’s Independent Party had closely collaborated with each other in the Central Legislative Assembly and many Congress resolutions against the Government succeeded only on account of Jinnah’s support. Their relations during the elections were also friendly. Later, when after the elections in 1937, the Congress at first refused to accept office, and the Governors called the League leaders, as representing the next largest party, to form what we called interim Ministries Jinnah would not allow this. It is known that in some cases, the leaders of the League parties in the provincial legislatures e.g. Sir Ali Mohammad Khan Dehlavi in Bombay were quite willing – even keen – to become premiers but Jinnah overruled them. He would not profit by the Congress refusal to come in, or do anything, which might jeopardise the prospects of an effective League-Congress collaboration on which his heart was set.

The Congress party leaders, however, when it was their turn to be invited by the Governors, completely ignored the Muslim League. This must have hurt Jinnah; what followed was calculated to rouse his ire still further. The Congress Government had taken one false step in taking, as Muslim Ministers, persons who did not command the confidence of the Muslims in the legislature. This false step was succeeded by many more of the same type. In the absence of a true Muslim representative in the Cabinet, the congress Government had nobody to advise them about the views of the Muslims, when they took decision affecting the general population. The so-called “Muslim Minister” knew very well that he was governed by the Congress pledge, and the iron discipline of that party. He usually represented himself alone, and lacked that moral courage which comes from having “big battalions at one’s back.” In many cases, he was just a newcomer to the Congress ranks, avowedly for the sake of the office – and did not carry with his colleague in the Cabinet, anything of the influence which a Syed Mahmud or Yaqub Hassan would carry. Bereft of any following, and any mission, that he was to watch the Muslim interests – and in many cases, even the support of a contented conscience – the Muslim Minister was a pathetic figure, and deprived of his frank advice, the Congress Governments took several steps, which caused deep resentment amongst the Muslims – as well as by Hindu untouchables – and a committee has reported on the hardships, to which Muslims were exposed under the Congress rule.

The second half of the year 1937 was one of the darkest periods through which Indian Muslims have had to pass since 1857. Their central political organization had failed to show any effectiveness at the polls. Over the greater part of the country, where the Congress ministries held sway, they felt that the Hindu Raj had come. They suddenly realized that all the fears, which Sir Syed and Viqar-ul-Mulk had expressed about their future, were coming true. They were most disheartened and sore at heart. They saw no way out of their predicament, and thought that soon the Congress, with its vast organization, and the policy of corrupting a few ambitious, un-principled Muslims, would extend its sway over the Muslim majority provinces and the while country would be come a vast prison-house for them.

The prospects for the Muslims were most gloomy and many faint hearts began to suggest that they should settle with the Congress on its own terms. There was however one light which burned bright and clear. Jinnah has been called a proud and haughty person, and this trait of character may have caused him as his people occasional difficulties. This was, however, the time when just these qualities were needed. In the midst of the storm he stood like a rock. He was the proud representative of a proud people and he hurled defiance at the pretensions and the dreams of the Congress. He was not going to lower his flag to come to terms with the Congress. Far from his accepting conditions while being offered seats in the Congress Governments, it would be he, who would impose conditions!

Indian Muslims are not likely to forget the resolve stand which Jinnah, without any visible following, without much support in the legislatures, and inspired solely by his sense of duty and his faith in his people, took at this juncture. But there was another great Muslim who, although in the background, gave Jinnah powerful and effective moral support. Jinnah had written about Iqbal.

“To me he was a friend, guide and philosopher, and during the darkest moments through which the Muslim League had to go, he stood like a rock and never flinched one single moment.”

Gradually the darkness began to lift. The Muslims saw the light and rallied round. Those in the Muslim majority provinces saw what was happening to their co-religionists in the Congress provinces and were deeply touched. They now realised that except through a powerful, All-India organization they had no means of saving themselves. So after having decisively defeated the League in the elections, the Muslim premiers of the Punjab, Bengal and Sind, came to terms with Jinnah and agreed to abide by the policy and decisions of All-India Muslim League in all-India matters.

These decisions which were announced at the annual sessions of the League, held at Lucknow, toward end of 1937, not only opened a new chapter for the League but marked a turning point in the history of Muslim India. The session was held in the face of heavy odds but, thanks to the help of the young Raja of Mahmudabad the arrangements were perfect, Jinnah, in his presidential address hurled defiance at the Congress, but now it was not the defiance of one who had nothing but faith and courage, to succour him. He had the premier of the Punjab and Bengal on his right and left and he knew that he had the support of almost every selfrespecting Muslim. The Muslim India had relied the round the rallying-post!

These decisions which were announced at the annual sessions of the League, held at Lucknow, toward end of 1937, not only opened a new chapter for the League but marked a turning point in the history of Muslim India. The session was held in the face of heavy odds but, thanks to the help of the young Raja of Mahmudabad the arrangements were perfect, Jinnah, in his presidential address hurled defiance at the Congress, but now it was not the defiance of one who had nothing but faith and courage, to succour him. He had the premier of the Punjab and Bengal on his right and left and he knew that he had the support of almost every selfrespecting Muslim. The Muslim India had relied the round the rallying-post!

Search For Security

The significance of the Lucknow session of the League was not on the Congress leaders. They realize that their treatment of the Muslims in the Congress provinces had been taken as a challenge by the entire Muslim India, which was prepared to meet it. The firm, disciplinarian policy of the iron dictator – the Sardar – had given results, quite different from what he expected. Thinking Hindus began to criticize the want of statesmanship shown by the Congress leadership in dealing with the Muslims. Tairsee, president of Hindu Gymkhana of Bombay, criticised, in the columns of Bombay Chronicle, the unstatesmanlike attitude which the Congress leadership had shown in refusing genuine representation to the Muslims in Congress Cabinets. Sardar Sardhul Singh Caveeshar of the Punjab expressed the same view in a long letter to Mahatma Gandhi. Sir Chiman Lal Sitalved criticised the unhappy development in the presidential address delivered in December 1937 at Calcutta session of All-India Liberal Federation and contrasted the unwise rigidity shown by the Congress leaders with the statesmanship displayed by the Muslim premier like Sir Sikandar Hayat.

The Congress leaders realized that they had blundered and appeared willing to take Muslim representatives in the Congress Cabinet on less exacting terms. Now it was Jinnah’s turn to be firm and unbending. The numerous unity talks which started between him and the Congress leaders, usually broke down on the question of the representative character of the Muslim League. His plea was that in 1916, when alone there was an agreement between Hindus and Muslims, the League had been taken as the sole and the authoritative representative of the Muslims and the Congress should now acknowledge its position in the same way. This, the Congress considered incompatible with its claim of speaking on behalf of entire India, and the negotiations broke down. Perhaps the truth in that what had happened in 1937, had not only embittered Jinnah but had finally convinced him that there was no safety for the Muslims in the goodwill of the Congress or the Hindus.

S.M. Ikram was a member of the Indian civil service and after partition held a number of important positions in the civil service of Pakistan. He has also published books in both Urdu and English on a variety of topics related to the history and culture of the Muslims of the subcontinent. In the excerpt quoted above, taken from a series of biographical sketches of Indian Muslim leaders, he discusses of the re-organization of the Muslim League in the thirties under the leadership of Jinnah.

Source: Muhammad Ali Jinnah Makers of Modern Pakistan. Edited by: Sheila McDonough (Sir George Williams University) D.C. Health and Company, Lexington, Massachusetts, USA.