Obituary - The Times

Quaid-e-Azam’s Fight Against Death

These revelations are made in a recently published book “The Story of Partition” written by two eminent French authors who traveled some 2.5 lakh meters to collect the material for the book. The research took them four years during which period they interviewed as many as 2,500 persons belonging to the pre-partition era.

The Quaid’s physician in Paris is reported to have told the authors that he had to keep a round the clock vigil to ensure that the x-ray films did not fall into the hands of the Britishers, who might use the Quaid’s disease to change the whole complexion of the political situation in the sub-continent.

The year 1946, it may be recalled, was the most eventful year engagement with the fast changing course of events, together with the brightening of the prospects of victory, exerted enormous physical and mental strains on the Quaid. It was he alone to whom the people looked for guidance and inspiration.

Quaid-e-Azam M.A. Jinnah: A Guardian of Minorities

The role of Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah in the annals of Indo-Pakistan has variously been interpreted implying a variety of perspectives which have earned him a good deal of prestigious titles like the Ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity, as a strategist, etc. A survey of literature, however, reveals that Jinnah’s vision regarding minority rights and his struggle and strategies to safeguard their interests perhaps is the most ignored perspective. Jinnah’s vision about minority’s place in the institutional frame of the Imperial Government in British India and later in the Sovereign State of Pakistan rather becomes more important in the context of growing discontent among religious minorities of Pakistan.1 This situation has earned a scientific inquiry of Jinnah’s vision in this regard since his whole political career seems to be a struggle for minority rights, especially the Muslims.

The Muslim community in the Indian subcontinent during the colonial era constituted the largest minority. About 25% of the total population, the Muslim community, had spread throughout the country. However, their population was distributed as such that they formed majority in five provinces, whereas the Hindus commanded clear majority in seven out of twelve provinces.2 The Muslims being a religious and political minority had distinct interests, which were not shared by the dominant community of the Hindus. Thus, it had necessitated additional constitutional and legal protection of the Muslims against the Hindus.

The first set of demands of the Muslim community for its constitutional and legal safeguards was manifested in the Simla Deputation of 1906. The address presented by them before the Governor General of India stated explicit terms: it cannot be denied that we Mohammadans are a distinct community with additional interests of our own which are not shared by other communities, and these have hitherto suffered from the fact that they have not been adequately represented…they have often been treated as though they were inappreciably small political factors…..3

Mr Jinnah Vs Gandhi

Mr Mohammad Ali Jinnah was a straight forward person and used to say harsh and to the point things to Gandhi.

Followers of Gandhi once asked him, "Mr Jinnah is very outspoken and tell you whatever he likes, why don't you reply him in the same manners""

Gandhi replied " I hear from one ear and take out from another ear"

Followers of Mr Jinnah informed him about Gandhi's remarks

Mr Jinnah replied " This is only possible when in between the both ears nothing exists"

.

What Allama Dr. Mohammad Iqbal was for Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah?

Message of condolence on the death of Sir Muhammad Iqbal, Calcutta, April 21, 1938

The Star of India, April 22, 1938

Mr. M. A. Jinnah issued the following condolence message on the death of Allama Iqbal:

I am extremely sorry to hear the sad news of the death of Sir Muhammad Iqbal. He was a remarkable poet of world wide fame and his work will live for ever. His services to his country and the Muslims are so numerous that his record can be compared with that of the greatest Indian that ever lived. He was an ex-President of the All-India Muslim League and a President of the Provincial Muslim League of the Punjab till the very recent time when his unforeseen illness compelled him to resign. But he was the staunchest and the most loyal champion of the policy and programme of the All-India Muslim League.

To me he was a friend, guide and philosopher and during the darkest moments through which the Muslim League had to go, he stood like a rock and never flinched one single moment and as a result just only three days ago he must have read of been informed of the complete unity that was achieved in Calcutta of the Muslim leaders of the Punjab and today I can say with pride that the Muslims of Punjab are wholeheartedly with the League and have come under the flag of the All-India Muslim League, which must have been a matter of greatest satisfaction to him. In the achievement of this unity Sir Muhammad Iqbal played a most signal part. My sincerest and deepest sympathy go out to his family at this moment in their bereavement in losing him, and it is a terrible loss to India and the Muslims particularly at this juncture.

Mr. Jinnah in the Courtroom

Mr. Frank Moraes, Chief Editor of The Indian Express has described Quaid-i-Azam in the following words: “Watch him in the court room as he argues a case. Few lawyers command a more attentive audience. No man is more adroit in presenting his case. If to achieve the maximum result with minimum effort is the hallmark of artistry, Mr. Jinnah is an artist in his craft. He likes to get down to the bare bones of a brief. In stating the essentials of a case, his manner is masterly. The drab courtroom acquires an atmosphere as he speaks. Juniors crane their necks forward to follow every movement of his tall, well groomed figure; senior counsels listen closely; the judge is all attention.”

Thomas Jefferson and Mohammad Ali Jinnah: Dreams from two founding fathers

By Akbar Ahmed

| Mohammad Ali Jinnah |

These are the words of a founding father -- but not one of the founders that America will be celebrating this Fourth of July weekend. They were uttered by Mohammed Ali Jinnah, founder of the state of Pakistan in 1947 and the Muslim world's answer to Thomas Jefferson.

When Americans think of famous leaders from the Muslim world, many picture only those figures who have become archetypes of evil (such as Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden) or corruption (such as Hamid Karzai and Pervez Musharraf). Meanwhile, many in the Muslim world remember American leaders such as George W. Bush and Dick Cheney, whom they regard as arrogant warriors against Islam, or Bill Clinton, whom they see as flawed and weak. Even President Obama, despite his rhetoric of outreach, has seen his standing plummet in Muslim nations over the past year.

Blinded by anger, ignorance or mistrust, people on both sides see only what they wish to see, what they expect to see.

Despite the continents, centuries and cultures separating them, Jefferson and Jinnah, the founding fathers of two nations born from revolution, can help break this impasse. In the years following Sept. 11, 2001, their worlds collided, but the things the two men share far outweigh that which divides them.

Each founding father, inspired by his own traditions but also drawing from the other's, concluded that society is best organized on principles of individual liberty, religious freedom and universal education. With their parallel lives, they offer a useful corrective to the misguided notion of a "clash of civilizations" between Islam and the West.

|

| Thomas Jefferson |

The two were born subjects of the British Empire, yet both led successful revolts against the British and made indelible contributions to the identities of their young nations. Jefferson's drafting of the Declaration of Independence makes him the preeminent interpreter of the American vision; Jinnah's first speeches to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan in 1947, from which his statement on freedom of religion is drawn, are equally memorable and eloquent testimonies. As lawyers first and foremost, Jefferson and Jinnah revered the rule of law and the guarantee of key citizens' rights, embodied in the founding documents they shaped, reflecting the finest of human reason.

Particularly revealing is the overlap in the two men's intellectual influences. Jefferson's ideas flowed from the European Enlightenment, and he was inspired by Aristotle and Plato. But he also owned a copy of the Koran, with which he taught himself Arabic, and he hosted the first White House iftar, the meal that breaks the daily fast during the Muslim holy days of Ramadan.

And while Jinnah looked to the origins of Islam for political inspiration -- for him, Islam above all emphasized compassion, justice and tolerance -- he was steeped in European thought. He studied law in London, admired Prime Minister William Gladstone and Abraham Lincoln, and led the creation of Pakistan without advocating violence of any kind.

In political life, the two suffered accusations of inconsistency: Jefferson for not being robust in defending Virginia from an invading British fleet with Benedict Arnold in command; Jinnah for abandoning his role as ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity and becoming the champion of Pakistan.

The controversies did not end with their deaths. Jefferson's views on the separation of church and state generated animosity in his own time and as recently as this year, when the Texas Board of Education dropped him from a list of notable political thinkers. Meanwhile, hard-line Islamic groups have long condemned Jinnah as a kafir, or nonbeliever; "Jinnah Defies Allah" was the subtitle of an exposé in the December 1996 issue of the London magazine Khilafah, a publication of the Hizb ut-Tahrir, one of Britain's leading Muslim radical groups. (Jinnah's sin, according to the author, was his insistence that Islam stood for democracy and supported women's and minority rights.)

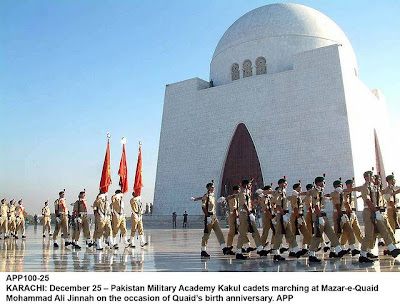

But today such opinions are marginal ones, and the founders' many contributions are commemorated with must-see national monuments -- the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, Jinnah's mausoleum in Karachi -- that affirm their standing as national heroes.

If anything, it is Jefferson and Jinnah who might be critical. If they could contemplate their respective nations today, they would share distress over the acceptance of torture and suspension of certain civil liberties in the former; and the collapse of law and order, resurgence of religious intolerance and widespread corruption in the latter. Their visions are more relevant than ever as a challenge and inspiration for their compatriots and admirers in both nations.

Jefferson and Jinnah do not divide civilizations; they bridge them.

akbar@american.edu

Akbar Ahmed is the Ibn Khaldun chair of Islamic studies at American University's School of International Service. This essay is adapted from his new book, "Journey Into America: The Challenge of Islam."

Foreign Policy of Pakistan: 1947-48

by Saeeduddin Ahmad Dar

Pakistan came into being under most unfavourable circumstances. Few weeks before independence, anti-Muslim riots broke out in East Punjab and a number of adjoining princely states. The riots which were “long planned and directed from a very high level”, were nothing less than “a war of extermination against the Muslim minority”.1 Soon the riots spread to Delhi, where it became impossible for a Muslim “to move freely without risk to his life”.2 Consequently, millions of Muslims from India were forced to take refuge in Pakistan. The immediate problem of the Government of Pakistan, was, therefore, to provide them food and shelter. It was by no means an easy task for a state, which had literally started from a scratch. At the same time, the planned migration of the Hindus, who controlled the economic resources of the areas constituting Pakistan before independence, crippled Pakistan’s economy.

Pakistan came into being under most unfavourable circumstances. Few weeks before independence, anti-Muslim riots broke out in East Punjab and a number of adjoining princely states. The riots which were “long planned and directed from a very high level”, were nothing less than “a war of extermination against the Muslim minority”.1 Soon the riots spread to Delhi, where it became impossible for a Muslim “to move freely without risk to his life”.2 Consequently, millions of Muslims from India were forced to take refuge in Pakistan. The immediate problem of the Government of Pakistan, was, therefore, to provide them food and shelter. It was by no means an easy task for a state, which had literally started from a scratch. At the same time, the planned migration of the Hindus, who controlled the economic resources of the areas constituting Pakistan before independence, crippled Pakistan’s economy.

The problems of the new state were enhanced by the hostile policy of the Government of India. In October 1947, Field Marshal Claude Auchinleck reported to the British Prime Minister Attlee: “The present Indian cabinet are implacably determined to do all in their power to prevent the establishment of Dominion of Pakistan on a firm basis”.3 To another foreign observer India seemed hell bent on “to destroy Pakistan as rapidly as possible so as to restore it to the dominion of Delhi”.4 Such conclusions were strengthened by actions of Government of India. For instance, India retained much of Pakistan’s share of the assets of the undivided India.5 She refused to deliver more than ninety seven percent of Pakistan’s share of military stores.6 The Government of India instructed its Reserve Bank (which according to an agreement made at the time of partition, was supposed to act as banker as currency authority both for India as Pakistan up to 1 October 1948) not to credit the Government of Pakistan with 550 million rupees of cash balance, which was due to her out of her share of 750 million rupees.7

The Indian occupation of the princely states of Junagadh, Manavader and Mangrol, which had acceded to Pakistan, and the dispatch of Indian troops to Jammu and Kashmir posed serious threat to the security of Pakistan. India seemed to be on war path. Even Gandhi, ‘the great apostle of non-violence’ talked about war with Pakistan.8

To deal effectively with these colossal internal problems and a hostile stronger neighbour the new state required a large army efficient and experience Civil Service. But at the time of independence , Pakistan had no army worth the name or even a civil service. In the latter category, in particular, there were not many senior officers. Amongst the officials who had ‘opted’ for Pakistan there was hardly any Muslim I.C.S. officer above the rank of a Deputy Secretary.

The situation in the newly created Ministry of External Affairs and Commonwealth Relations was even worse.9 Amongst the one hundred and fifty odd officials of the three major departments – the Political and State Department, the Department of External Affairs, and the Department of Commonwealth Relations – who came to the same of Pakistan, more than a third were peons. Among the officers only four Muslims and five British nationalists came to Pakistan. When the Foreign Office was established, there was only one Joint Secretary and two Deputy Secretaries and they were all British nationals. Later, two Muslim I.C.S. Officers who had served on the Partition Committee, were also taken in as a Deputy Secretaries. Ikramullah, who held the rank of a mere Deputy Secretary in the Government of India, was exalted to the position of Foreign Secretary. He had not experience of international relations or the working of a department dealing with external affairs. The result was that Joint Secretary, T.B. Creag Coen, who had served in the Indian Political Service, dominated the Foreign Office and his opinion was regarded as the last word.

Until December 1947, Pakistan did not have a full time Foreign Minister. Officially, Liaqat Ali Khan held the portfolio of External Affairs, but in practice all papers were put up to Quaid-i-Azam for information or decision. Quaid-i-Azam’s pre-occupation with internal problems and his failing health, did not give him to concentrate on foreign relations. Such a situation could not go on for long. Therefore, in December 1947, Zafarullah Khan, who had some experience in external affairs was appointed as Foreign Minister Zafarulla who had worked as Indian Political Agent in China, represented India in the U.N on Palestine Problem, and later on 1947 had led Pakistan’s delegation to the U.N. General Assembly. Still the policy decisions continued to rest with Quaid-i-Azam. Even during his last days at Ziarat, Ikramullah, the Foreign Secretary, regularly visited him to apprise the Quaid of the latest developments and to seek his guidance.

Due to shortage of trained personnel, Pakistan could not establish diplomatic relations with more than six countries. In the initial months Habib Rahimatulla was appointed High Commissioner in London and I.H. Ispahani, Aurangzeb Khan and I.I. Chundrigar as ambassadors to Washington, Rangoon and Kabul respectively. The embassies at Tehran and Cairo remained without ambassadors till 1948, when Raja Ghazanfar Ali and Abdul Sattar Seth presented their credentials. None of the ambassadors appointed had any experience in international politics and diplomacy.

Moreover in 1948 the Public Service Commission for the first time selected thirteen persons to be appointed as officers in Pakistan Foreign Service. In order to fill senior posts it was decided to induct officers from other departments. This group lacked experience in diplomacy and were of “uneven quality”.10 It could not be expected from these ‘diplomats’ sitting in the foreign office or serving in the mission to give a lead or even to assist the politicians in the formation of a foreign policy. No wonder, Pakistan in its first year, could not formulate a foreign policy.

However, it can be said that Pakistan carried over the policy of the All India Muslim League towards the Muslim world, and particularly towards Palestine. Muslim League’s policy was best stated by Quaid-i-Azam in October 1942, on the occasion of the Eid-ul-Fitar. He had declared: “while we are engaged in our struggle for freedom and independence, let us not forget our brethren who in other parts of the world are going likewise”.11 Regarding the Arabs he said: “The Muslims of India will stand solidly and will help the Arabs in every way they can in their brave and just struggle that they are carrying on against all odds”.12

Between 1933 and 1946 the Muslim League passed eighteen resolutions in support of the Muslims of Palestine.13 In November 1933, the Muslim League passed a resolution asking the British Government to immediately withdraw the Balfour Declaration as “it opposed the fundamental rights of the people entrusted to their British control”.14 In April 1934 the Council of the Muslim League resolved to send a deputation to wait on the Viceroy to lay before them the facts of how the Balfour Declaration would help the Jews and deprive the Arab inhabitants of their rights. The council also expressed its “whole hearted sympathy and support for the Arabs of Palestine”.15 When the Royal Commission recommended partition of Palestine Quaid-i-Azam strongly condemned it.16 The Muslim League demanded that the recommendations of the Royal Commission be withdrawn and asked the Government of India to instructs its representative as the Assembly of the League of Nations to demand annulment of the mandate and disassociate themselves from any decision tending “to perpetuate it and thus to violate the fundamental rights of the Arab inhabitants of Palestine to choose the form of Government best suited to their needs and requirements…17”. On the directive of the Muslim League the Muslims of British India, on 26 August 1938, observed ‘Palestine Day’. In October 1938 the Muslim League sent a four-member delegation to Egypt, to attend an “Arab Leader’s conference” in connection with Palestine. Two of them accompanied an ‘Arab delegation’ to London to discuss the problem with the British Government. The representatives of the Muslim League submitted a statement of the views of the Muslims of British India to the British Government. 18 Quaid-i-Azam made a strong representation to the Viceroy and had a number of interviews with him on the Palestine question.19 In July 1939 the Muslim League opened a ‘Palestine Fund’ for “the relief of the dependents of those, who lost their lives or suffered in the struggle for independence and for the protection of First Qibla of Musalmans”.20 In same year the day of Miraj was observed as ‘Palestine Day’21. On 23 March 1940, when the Muslims of British India met at Lahore and made the historic decision about their future, they expressed their concern on “the inordinate delay on the part of the British Government in coming to a settlement with the Arabs in Palestine”22. In 1945, another ‘Palestine Day’ was observed.23

Besides, Palestine, the Muslim League took up the cause of all the Muslims struggling for their independence and the preservation of their national sovereignty. In 1924, when it was speculated the Iraq would be placed under British mandate the Muslim League declared that Iraq was “a part of Jaziatul Arab and so such should not be left under non-Muslim control of the British as a mandatory power”.24 After the beginning of the Second World War when news were received that war activities might affect the independence of Egypt, Palestine, Syria and Turkey, the Muslim League proclaimed that “in the event of any attack upon Muslim countries, Muslim India will be forced to stand by them and give all the support it can”.25 The Muslim League took up the cause of Iran when Britain and the Soviet Union occupied Iranian territories during the war26. On 26 December 1943 the Muslim League passed a resolution demanding the independence of Ceraneca, Libya, Tripoli, Palestine, Syria, Lebanon, Moracco, Algeria and Tunis27. Quaid-i-Azam condemned the Dutch “imperialist hold” on Indonesia.28

After the creation of Pakistan the moral support given to the Muslim world by the All India League assumed the form of diplomatic support of the Government of Pakistan. The unity of the Muslim states was considered a must for the solution of their problems. Quaid-i-Azam believed that it was only by putting a united front that the Muslim states could “make their voice felt in the councils of the world”29. In order to achieve this objective, in October 1947, he sent Malik Feroz Khan Noon as his special envoy to some of the countries in the Middle East.30 This one-man delegation was the first official mission sent abroad by Pakistan. The aim of the mission was to introduce Pakistan, to explain the reasons of its creation, to familiarise them with its internal and external problems to get their support. Feroz Khan Noon, first visited Ankara, where he met President Ismat Inonu and other Turkish dignatories. He participated in the independence day celebrations of Turkey and gave an exclusive interview to the correspondent of Ulus. From Turkey he went to Syria. At Damascus he held discussions with Syrian leaders. From Damascus he went to Aman and met King Abdullah. On his way to Beirut he met Mufti Amin Al-Husaini, the Grand Mufti of Palestine, who had gone underground and was residing in the suburbs of Beirut. His next and last stop was Riyadh, where he was received by King Abdul Aziz Ibn-e-Saud. The King gave a banquet in Noon’s honour and placed his personal plane at his disposal to take him to Dahran on way to Karachi. Noon returned to Karachi in the first week of December. As there were no diplomatic channels available, Feroz Khan Noon sent his reports to his brother Malik Akbar Hayat Noon, who through Ikramullah delivered them to Quaid-i-Azam. Quaid-i-Azam did not give these reports to the foreign office and kept them with him. Unless these papers are made available nothing can be said with certainly about the extent of the success of the mission; but it is certain that this was the beginning of Pakistan’s close relations with Turkey, Jordan and Saudi Arabia, which continued to develop in the years to come.

Pakistan lent full diplomatic support to the cause of the Muslims of Palestine. When Pakistan became the member of the United Nations (30 September 1947), the Palestine question was already under active consideration of the United Nations. On the request of the United Kingdom the Secretary General summoned the first special session of the General Assembly. On 15 May 1947 the General Assembly created the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP). The UNSCOP recommended that the Mandate be terminated and Palestine granted independence at the earliest practicable date. The report contained a majority proposal for the ‘Plan of Partition’ with an ‘Economic Union’ and a minority proposal for a ‘Plan for a Federal State of Palestine’31 On 23 September the General Assembly established, the ‘Ad Hoc Committee on Palestine Question’ to consider the report of UNSCOP.

In the Ad Hoc Committee Pakistan opposed the ‘Partition Plan’. Zafarulla claimed that the Balfour Declaration was “invalid”32. He suggested that the Committee should strive “to find a solution which would be in accord with the freely-expressed wishes of the people concerned…33. He declared that Pakistan was utterly and uncompromisingly opposed to the partition of Palestine”34 He warned the Committee that the partition of Palestine “might provoke a conflict which the United Nations would find difficult to contain”35.

On 23 September 1947, the Ad Hoc Committee established two sub-committees. ‘Sub-Committee I’ was entrusted with drawing up a detailed plan based on the majority proposals of UNSCOP; and ‘Sub Committee 2’ to draw up a detailed plan in accordance with the proposals of Saudi Arabia and Iraq for the reorganisation of Palestine as an independent Unitary State36. Pakisan was a member of Sub-Committee 2’. On 28 October 1947, on the resignation of the representative of Columbia, Zafarullah was elected its Chairman. In its report ‘Sub-Committee I’ recommended “the adoption and implementation” of the ‘Plan of Partition’ with an ‘Economic Union’37. Sub-Committee 2 raised legal, constitutional and political objections and asked the General Assembly to refer them to the International Court of Justice. The Committee stressed that the United Nations had “no authority under the Charter to partition Palestine or any way to impair its integrity against the wishes of the majority of the people”38.

The Committee proposed a “unitary and sovereign” state for Palestine.39 Commenting on the ‘Partition Plan’ proposed by the Sub Committee I’ Zafarulla said that Pakistan could not accept it because “it had no legal basis and was unworkable…and instead of settling the dispute, served to add to the exciting difficulties.”40

The Ad Hoc Committee did not accept the proposals of ‘Sub-Committee 2’ and include in its repot the draft resolution of ‘Sub-Commttee I’ embodying the ‘Plan of Partition’ with an ‘Economic Union’, with various amendments.

Pakistan made an eleventh hour attempt to convince the United States, which was the main supporter of the ‘Partition Plan’ and was exerting pressure on small states, to vote for it, that the decision to partition Palestine was “ultra vires of the United Nations Charter” and was “basically wrong and invalid in law”. Quaid-i-Azam sent a cable to President Truman and appealed to him, and through him to the people of the United Sates to uphold the right of the Arabs. He wrote: “The Government and the people of the America can yet save this dangerous situation by giving a correct lead and thus avoid the greatest consequences and repercussions”41. The United States, which was more concerned with her interests in the Middle East than the moral and legal rights of the Arabs, managed to get two third votes in favour of the ‘Partition Plan’. Pakistan was one of the thirteen members which cast negative votes. Commenting on the role played by the United States Zafarulla said that “The Partition Plan could be called a United States’ rather then a United Nation’ decision.42 Pakistan did not take part in the election of the United Nations Commissions which was set up to implement the decision of the General Assembly. When Israel was admitted to the United Nations Pakistan opposed and voted against it; and refused to recognise the state of Israel.

The Constituent Assembly of Pakistan (which also functioned as its parliament) adopted a motion expressing deep sympathy with the people of Palestine in their “struggle in the cause of justice and peace in Palestine”43. Later, when foreign policy of Pakistan took a shape, support to the cause of the Muslims in general and that of Palestine in particular became its cardinal principle.

By 1949, Pakistan, to a great extent, overcame its major internal problems and for the first time gave a serious consideration to the formulation of a definite and determined foreign policy. During the formative phase Pakistan explored different alternatives. Liaquat Ali Khan’s acceptance of the Russian invitation to visit Moscow, Pakistan’s attempts to institutionalise its relations with the Muslim World, and Liaquat’s visit to the U.S.A and Canada were earliest attempt in this direction.

References

- G.W. Choudhury, Pakistan’s Relations with India 1947-66, London, 1968, PP. 41-42.

- John Connel, Auchinleck, London, 1956, pp. 920-22.

- Ibid.

- Vincent Shean in New York Herald Tribune, 16 June 1948, quoted by S.M. Burke, Mainprings of Indian and Pakistani Foreign Policies, Karachi, 1957, p. 58.

- Ian Stephens, Horned Moon, London, 1953, p. 215.

- Connel, op. cit., PP. 220-22.

- Choudhury, op. cit., P. 63.

- Ibid., P. 50.

- The information about the condition of the foreign office is based on author’s interviews with the officials who were in the foreign office at that time.

- Burke, op. cit., P. 77.

- Jamiluddin Ahmed, ed., Speeches and Statements of Mr. Jinnah Vol. I, Lahore, 1960, P. 421.

- Ibid., P. 36.

- For the Texts of these Resolutions see; Resolutions of the All India Muslim League, May 1924 to December 1943, in Syed Sharifuddin Pirzada, Foundations of Pakisan: All India Muslim League Documents 1906-1947, Vol. II, Karachi, 1970.

- Resolutions of the All India Muslim League from May 1924 to December 1936, Delhi?, n.d., p. 59.

- Quoted by Syed Sharifuddin Pirzada, ‘Quaid-i-Azam and Islamic Solidarity’, Zahid Malik, ed., Re-Emerging Muslim World, Lahore, 1974, PP. 28-29.

- See. Ahmed op. cit., PP. 34-36.

- Resolutions of the All India Muslim League from October 1937 to December 1938, Delhi? 1944, Delhi? 1944, PP. 1-2. PP. 1-2.

- For details of the activities of the delegation see Chaudhuri Khaliquzzaman, Only if they know it? Karachi, 1965, PP. 15-18.

- Malik op. cit., p. 30.

- Resolutions of the All India Muslim League from December 1938 to March 1940, Delhi? N.d., p. 12.

- Ibid., P. 22.

- Ibid., P. 49.

- Malik, op. cit., P. 31.

- Resolutions of the All India Muslim league from May 1924 to December 1936, Delhi,? n.d., p. 21.

- Resolution of the All India Muslim League from March 1940 to April 1941, Delhi? n.d. p. 20.

- Resolution of the All India Muslim League from March 1941 to April 1942, Delhi?, n.d., P. 5.

- Resolution of the All India Muslim League from May 1943 to December 1943, Delhi,? n.d., PP. 29-30.

- Jamiluddin Ahmed, ed., Speeches and Writings of Mr. Jinnah Vol. II, Lahore, 1964, PP. 301-2.

- Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Speeches as Governor General 1947-48, Karachi, n.d., P. 26.

- The information about the visit is based on author’s interview with Mr. Farooq, who accompanied Malik Feroz Khan as his Private Secretary.

- United Nations Special Committee on Palestine Report to the General Assembly Vol. I, New York, 1947, P. 42.

- U.N. Document No. A/AC-14/SR-7, 7 October 1947, P. 2.

- Ibid., P. 8.

- U.N. Document No. A/AC-14/SR-12, 13 October 1947, p. 6.

- U.N. Document No. A/AC-14/SR-30, 24 October 1947, P. 7.

- Year Book of the United Nations 1947-48, New York, 1949, pp. 237-38.

- Official Record of the Second Session of the General Assembly Ad Hoc Committee on the Palestinian Question, New York

- Ibid., P. 290.

- Ibid., P. 302.

- U.N. Document No. A/AC-14/SR-31, 24 November 1947, P. 4.

- Malik, op. cit., P. 32.

- Official record of the Second Special Session of the General Assembly Vol. II, New York, 1948, p. 51.

- Constituent Assembly (Legislature) Debates Vol. I, Karachi, P. 891.

Source: World Scholars on Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

Edited by: Ahmad Hasan Dani, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan 1979.

Eid-ul- Azha- A symbol of Islamic spirit and sacrifice (24th Oct 1947)

God often tests and tries those whom he loves. He called upon Prophet Ibrahim to sacrifice the object he loved most. Ibrahim answered the call and offered to sacrifice his son. Today too, God is testing and trying the Muslims of Pakistan and India. He has demanded great sacrifices from us. Our new-born State is bleeding from wounds inflicted by our enemies. Our Muslim brethren in India are being victimized and oppressed as Muslims for their help and sympathy for the establishment of Pakistan. Dark clouds surround us on all sides for the moment but we are not daunted, for I am sure, if we show the same spirit of sacrifice as was shown by Ibrahim, God would rend the clouds and shower on us His blessing as He did on Ibrahim. Let us, therefore, on the day of Eid-ul-Azha which symbolizes the spirit of sacrifice enjoined by Islam, resolve that we shall not be deterred from our objective of creating a State of our own concept by any amount of sacrifice, trials or tribulations which may lie ahead of us and that we shall bend all our energies and resources to achieve our goal. I am confident that in spite of its magnitude, we shall overcome this grave crisis as we have in our long history surmounted many others and notwithstanding the efforts of our enemies, we shall emerge triumphant and strong from the dark night of suffering and show the world that the State exists not for life but for good life.

On this sacred day, I send greetings to our Muslim brethren all over the world both on behalf of myself and the people of Pakistan. For us Pakistan, on this day of thanksgiving and rejoicing, has been overshadowed by the suffering and sorrow of 5 million Muslims in East Punjab and its neighborhood. I hope that, wherever Muslim men and women foregather on this solemn day. They will remember in their prayers these unfortunate men, women and children who have lost their dear ones, homes and hearths and are undergoing an agony and suffering as great hand cruel as any yet inflicted on humanity. In the name of this mass of suffering humanity I renew my appeal to Muslims wherever they may be, to extend to us in this hour of our danger and need, their hand of brotherly sympathy, support and co-operation. Nothing on earth now can undo Pakistan.

The greater the sacrifices are made the purer and more chastened shall we emerge like gold from fire.

So my message to you all is of hope, courage and confidence. Let us mobilize all our resources in a systematic and organized way and tackle the grave issues that confront us with grim determination and discipline worthy of a great nation.

Nations are born in the hearts of poets!!!

The poetry of Allama Iqbal was a breath of fresh air throughout Pakistan Movement... ...This is the historical and extremely memorable pic o...

-

In 1913 the Quaid-i-Azam joined the All India Muslim League without abandoning the membership of the Congress of which he had been an active...

-

Quaid-e-Azam addressing a group of students 1. My young friends, I look forward to you as the real makers of Pakistan, do not be exploit...