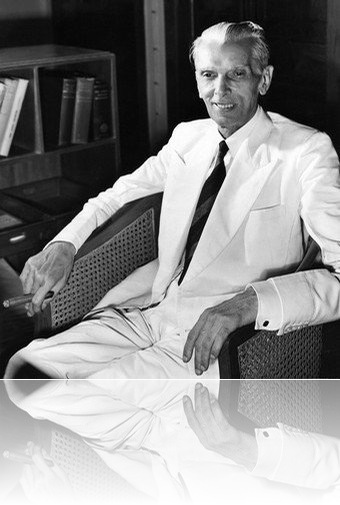

Life of the Quaid-i-Azam was not be bed of roses. The struggle he had begun in his early  days continued till the end. At the age of 70 age, after a long hard and distinguished career in law and politics, when most people in the evening of their life look forward to days of retirement and leisure, the Quaid had accepted the challenge and responsibilities of head of a new State he had founded. Constant toil in the service of his people had had taken heavy toll of Quaid’s failing health, but he insisted on keeping his finger on the pulse of the nation. He was soul that thirsted for service in a body that was worn out by overwork and ill-health. Despite the advice of his doctors, he did not spare himself, refusing to take rest or respite. He worked harder and harder as the end approached. In the words of Fatima Jinnah his constant companion and sister, “Nature had gifted him with a giant’s strength in so far as his determination to achieve the tasks that he had set for himself were concerned, but it had clothed that will in a frail body, unable to keep pace with the driving force of his restless mind and will. It was bitter to be afflicted with health that could not stand the rigours of a tumultuous life in the face of overwhelming odds, and to be gifted with a tenaciousness that wanted to triumph over all obstacles to lead his people to their ultimate destiny.

days continued till the end. At the age of 70 age, after a long hard and distinguished career in law and politics, when most people in the evening of their life look forward to days of retirement and leisure, the Quaid had accepted the challenge and responsibilities of head of a new State he had founded. Constant toil in the service of his people had had taken heavy toll of Quaid’s failing health, but he insisted on keeping his finger on the pulse of the nation. He was soul that thirsted for service in a body that was worn out by overwork and ill-health. Despite the advice of his doctors, he did not spare himself, refusing to take rest or respite. He worked harder and harder as the end approached. In the words of Fatima Jinnah his constant companion and sister, “Nature had gifted him with a giant’s strength in so far as his determination to achieve the tasks that he had set for himself were concerned, but it had clothed that will in a frail body, unable to keep pace with the driving force of his restless mind and will. It was bitter to be afflicted with health that could not stand the rigours of a tumultuous life in the face of overwhelming odds, and to be gifted with a tenaciousness that wanted to triumph over all obstacles to lead his people to their ultimate destiny.

His political activities and responsibilities had increased manifold during the last ten years of his life, when he had already entered the morning [?] of his old age. Work, work and more work. He drained away the last reserves of his energy like a spendthrift child of nature. Alarmed at his poor health, when I sometimes begged of him not to work such long hours and to give up for some time his constant and whirlwind tours that carried him from one end of India to another, he would say, “Have you ever heard of a General take a holiday, when his army is fighting for its very survival on a battlefield?” He had the reputation of demolishing a well-build up case with one sentence, and what match could I be for him when it came to arguments? On such occasions I abandoned logic for sentiment, “But your life is precious; and you must take good care of it.” With a distant look in his eyes, he said, “What is the health of one individual, when I am concerned with the very existence of ten crore Muslims of India? Do you realize how much is at stake?” This was enough to silence sentimentalism, and he plunged himself deeper and deeper into the stormy ocean of political struggle to the utter neglect of his health.

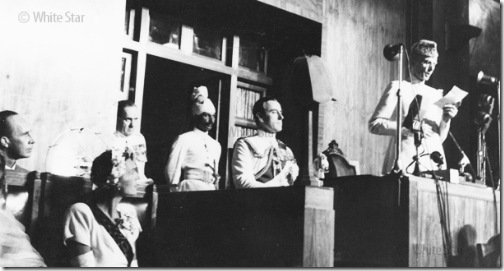

Although the Quaid-i-Azam never rested a moment after he had become the Governor-General and literally worked himself to death, his first months were the busiest and most anxious. War in Kashmir, ill-equipped armed forces, stagnant economy, empty treasury, paralyzed administration, refugees problem, and myriads of national and international problems had taken a heavy toll of Quaid’s health. However, it was a period of great trial and he had been unnerved, then Pakistan would have succumbed in the very hour of its birth. But the Quaid exerted himself to the utter neglect of his health and thundered in these uncertain days, “Pakistan has come to stay”, and, as everyone knows, it stayed and shall stay. But at what grievous cost to himself.

During February and March of 1948, Quaid-i-Azam still worked long hours at his desk. His secretary at this time has said, “His seriousness was contagious: there was no lightness or humour in our work. When Bills arrived for him to sign, he would go through them sentence by sentence” . The Quaid-i-Azam, however, continued to go through every minute administarative details of the state. He had his eyes on every aspect of the structure of Pakistan. Despite of his ill-health, he toured the country extensively. In February, 1948, he visited Baluchistan. In March, he flew the thousand miles to East Pakistan, where he endured a Programme of receptions, reviews and speeches, during several days. From April 15 for seven days the Quaid-i-Azam was on the North West Frontier, where there were more receptions, reviews and speeches: when he returned to Karachi he was too ill to work at his desk for very long. Sir Francis Mudie, one of Quaid-i-Azam’s last guest in Karachi has recalled, “I stayed with him for a few days late in May, he was very ill and spent most of the time in bed”.

One morning, also in February, Mr. Ian Stephens went to see the Quaid, He wrote afterwards, “…at that time, though no one realized it, the creator of Pakistan was dying, his lungs riddled with the unsuspected tuberculosis which a few months later killed him”.

To escape from the heat and humidity of Karachi and on the advice of his personal physician, the Quaid decided to fly to Quetta. In June, the Quaid moved, to a bungalow at Ziarat, eighty miles from Quetta. Lt. Mazhar Ahmed, one of his A.D.C.s describing Quaid-i-Azam’s days at Ziarat wrote, “Here was neither the heat of Karachi nor the formality of the Governor-General’s House. Here the Governor-General was just Quaid-i-Azam, and Quaid-i-Azam was just a man on a holiday. In the sitting room jokes were cracked, yarns were spun, discussions were prolonged, and even the A.D.Cs talked”.

According to Lt. Mazhar Ahmad, the Quaid-i-Azam was in a happy mood during the first days of his stay in Ziarat, “he had a sharp sense of humour and was full of jokes and anecdotes for all occasion. At one time he was talking of his visit to the Jacko Mill in Simla and spoke of the monkeys that dwelt there. He had some peanuts in his pocket and threw a handful to a large number of monkeys at one place. He was surprised to see that no monkey moved; there was no mad rush amongst them. The mystery was soon solved when a big fat monkey moved down from a tree towards the peanuts and the monkey gave way and stood in a line in silence, all the chirping having suddenly ceased. This fat monkey was their leader for whom they had exhibited so much discipline and respect. Even monkeys had discipline!”.

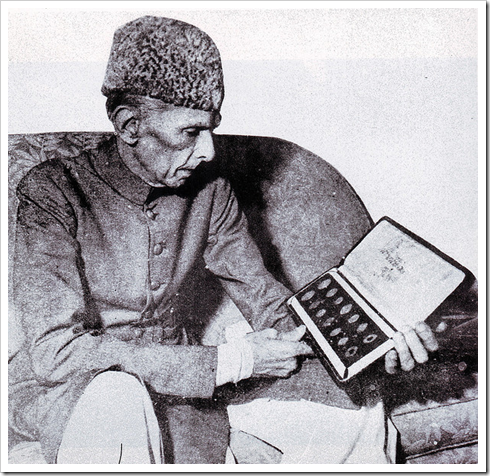

The Quaid-i-Azam knew no rest even during his stay in Ziarat. Lt. Mazhar Ahmad has said, “We raised the Governor-General’s dark blue flag over the quite house and hoped that the Quaid would rest. But it was not in his nature. The black dispatch-boxes arrived each day from Karachi, with M.A.J. stamped on them, in gold. They were ful of work to be done. My clearest memory of his is of his slim hands, busy with papers”.

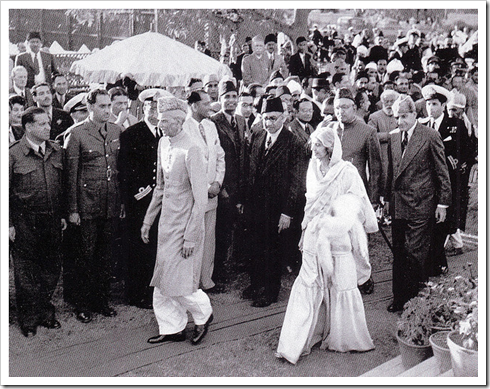

Some days later, the Governor-General flew from Quetta to Karachi to perform the opening ceremony of the State Bank of Pakistan himself Accompanying his sister, he drove to the Bank in the State coach and delivered an impressive speech. In the archives of the Karachi broadcasting station, there is a gramophone record of the speech that the Quaid made on July 1, 1948. Whosoever, heard him on this occasion, realized Quaid-i-Azam was in bad health, his voice scarcely audible, pausing, coughing, as he proceeded with the text of his speech. He looked so pale and anaemic, but within that amaciated body there burnt the dazzling flame of genius.

Lt. Mazhar Ahmad has described the episodes of that day” Quaid-i-Azam was very weak and tired as he stepped into the coach. The thousands of people pressed towards him, as if they wished to touch him, but the outsiders made this impossible; so the near one extended their hands towards the coach – as if this would complete their ecstasy. When we arrived back at Government House, we climbed the stairs together and turned right, towards Mr. Jinnah’s room. After a few paces he dismissed me. At the top of the stairs I turned and saw him staggering towards his door. I know then how ill he was”.

After five days’ stay at Karachi, where he attended to some very important files, he went back to Quetta by air. Once again in Quetta requests began to pour in from various institutions and demands were made from so many individuals and leaders, who were anxious to see him. He felt dejected that his health could not permit him to oblige them . The Quaid, however, was in very bad health. Mir Laik Ali, who had come to see the Quaid in Quetta to take his definite attitude towards Hyderabad, writers: “It was a little before eleven o’ clock in the morning that I had reached Quetta. Every minute was hanging heavy on me… Most of the time I had spent with Miss Jinnah, hoping all along that the Quaid would soon recover enough to spare me a few minutes, Miss Jinnah kept frequently going into his room and returned disappointed each time that he was no better. Finally, she was able to convey to him that I was in Quetta and had been waiting for a long time in other room. The Quaid, she told me, only with great difficulty, waved his fingers indicating that his agony was too great”.

Quaid-i-Azam’s health, however, was bad and his doctors were worried. They decided to move him up to Ziarat, where it would be cooler than Quetta and decidedly more restful.

Back in the bungalow at Ziarat, twenty-three days after the opening of the State Bank, the Quaid had to yield to the constant care of Colonel Ilahi Bakhsh. He was reduced to a skelton weighing only 70 pounds . The Colonel Bakhsh found him ‘Shockingly weak and thin’ . Farrukh Amin, also on the Quaid’s staff at Ziarat wrote in the Dawn “Often in these days did I find him walking up and down his bedroom at dead of night”.

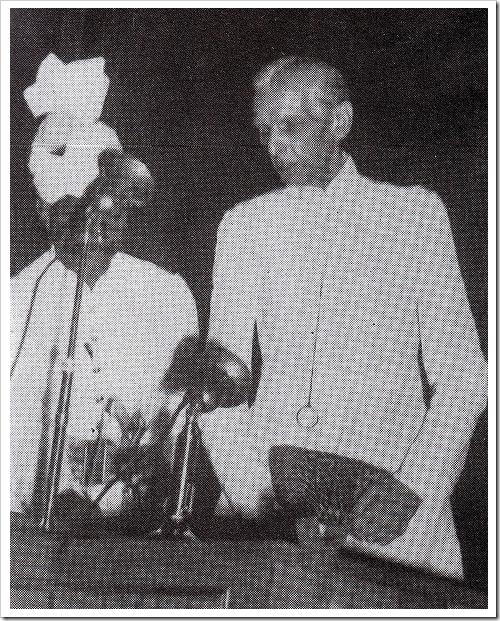

It was obvious to those around him at Ziarat that his health was fast deteriorating and Lt. Ahmad writes, “Miss Fatima Jinnah who for years had been the Quaid’s companion…in there days of ill-health looked after the Quaid-i-Azam with an affection and devotion which only a sister is capable of. Often she would go without sleep for nights on end, nursing him, humouring him, reading out to him, or just sitting by his side” .

S.M. Yusuf, his Private Secretary, who was close to him in those days, could discern the ravages that sickness was making on his health, but “sickness and failing health did not deter the Quaid-i-Azam from attending to his duty. He went on working to the very least and continued to deal with important State papers until his death”.

Saleh Mohammad was gardener at the Residency while Quaid-i-Azam stayed at Ziarat. Saleh Mohamad, describing Quaid’s days and daily routine at Ziarat, said, “Every day a table and a chair was laid for him in the lawn and he used to work. It was only a few days before his departure that he stopped working”. He said further, “The Quaid used to walk on the road that goes from the Residency to the swimming pool…. He used to walk slow and appreciate the juniper trees and wild flowers. After reaching the swimming pool he used to rest for some time and come back. Morning and evening, day after day, I went with him to the swimming pool and back to the Residency. There used to be a perpetual and unforgettable smile on his lips. I do not member having seen him without this smile, not even during the worst days of his illness…. He was terribly weak during those days of his illness but he did not lose hope” . In spite of his physical disabilities, the Quaid’s mind was active and alert, his spirit undamped and undaunted. He had won many battles in life; he faced his struggle against ill-health, with confidence. For, as Farrukh Amin, who was on his personal staff at Ziarat, wrote in the Dawn, they had seen the Quaid “so many times overcome the repeated illness by sheer willpower” . He had spent all his life treading the fiery path of struggle and defiance, and he did not want to end it in the ashes of defeat. He wanted to do so much, but he had so little time and strength left to do it.

The condition of Quaid-i-Azam was getting worse day by day. When the Doctor Bakhsh complained about his working habits during his last illness at Ziarat, he said “There is nothing wrong with me. I have stomach trouble and exhaustion due to overwork and worry. For forty years I have worked for fourteen hours a day, never knowing what disease was. For the last few years I have had annual attacks of fever and cough. My doctors in Bombay regarded these attacks as bronchitis….For the last years or two, however, they have increased, both in frequency and severity, and they are much more exhausting” . Quaid-i-Azam continued, “I do not think that there is anything organically wrong with me. If my stomach can be put right I will recover soon”.

But the tests of the doctors revealed a different story. Samples of the Quaid’s blood and sputum revealed on examination he was suffering from an infection of the lungs; it was thought he had been suffereing from it for about two years . Dr. Bakhsh had to break the grave news to the patient. After a short pause Quaid asked “Have you told Miss Jinnah? “yes”, he said, “No, you shouldn’t have done it. After all she is a woman. However, it does not matter. What is done is done” .

The Quaid-i-Azam wished that his sister alone should look after him. But he had to yield to the doctor and a nurse.

The nurse refused to tell him his temperature without the permission of the doctor. The Quaid felt pleased with her sense of discipline .

Under pressure from his doctors he was ultimately forced to give up all work connected with his official duties, as Governor-General. Disappointed, the Quaid kept himself away from his files, hoping he would be soon well to tackle the problems of Pakistan at its difficult period of history. No visitor was allowed to see him. But when M.A.H. Ispahani, who was to leave Pakistan within the next few days for Washington came to the Residency at Ziarat, an exception was made in his case. Having talked with Quaid-i-Azam for about half an hour, Ispahani, realized that the great leader was in very bad health indeed.

On July 29, X-ray photograph proved the damage to the Quaid’s lungs to be more terrible than was supposed. Ian Stephens writes, “Two-thirds of one lung seemed gone, and about a quarter of the other” . Sister Dunham was called in from Quetta to nurse him . On the first day when she wanted to adjust the pillows, he said, “Leave me alone’ don’t touch me” . She said, “All right, if you don’t wish to be helped, I won’t help you. The doctor has ordered…” “I don’t take orders; I give orders”, came the reply. Sister Dunham withdrew the word ‘order’ and said’ “The doctor has requested….” . Such outbursts of temper were due to the malignant disease. Otherwise he was not harsh, though it is admitted on all hands that he was a little hard, no doubt.

A few days later doctors found his blood pressure very low, and there was swelling on his feet . After a prolonged conference the doctors held that, in their opinion, the altitude of Ziarat was not good for him in that condition of health. On August 9, the doctors decided that the Quaid must be moved from the perilous heights of Ziarat, to Quetta. But the Quaid refused to travel unless he was properly dressed. A brand new coat, his pump shoes and his monocle had to be got ready. A fresh, snowy handkerchief was brought and unfolded; he held it between his fingers. For the whole of his life he enjoyed the distinciotn of being the best-dressed man. During his last days of illness he did not wish to tarnish that reputation.

When the Quaid, however, agreed to be shifted to Quetta, Lt. Ahmad, with the help of the Military A.D.C. and two Pathan servants, carried the Quaid’s frail body on a stretcher, down the stairs. Lt. Mazhar Ahmad has said, “When I lifted Quaid-i-Azam into the car, I had to hold him so close that his cheek was next to mine, and I could hear his soft breathing. I placed him on a mattress, but not quite where he would be table. I was still holding him when he said, ‘Mazhar, you are out of breath and I am out of breath. Let us Pause’. So I waited a moment, and then I moved him again. I asked him, “Are you comfortable’? He smiled, so sweetly, and then asked, “where is my handkerchief?” I found it from him; Then the others all got into cars and the journey began” .

However, Quaid-i-Azam left Ziarat for Quetta on 13th August, 1948 . The car moved slowly to avoid jerks and bumps, taking four hours to reach Quetta. As soon as they reached the residency to Quetta, the doctors examined him and found he had stood the journey well .

14th August, 1948, when Pakistan was to celebrate its first anniversary of independence, was drawing near and in spite of his doctor’s advice to the contrary, he was working on the message he wanted to give to the nation on that occasion. He was busy at it, his failing health notwithstanding . In spite of his physical disabilities, the Quaid’s mind was very active and alert. He worked in a tenser and more emotional way. His doctors never succeeded in stopping the onward rush of his mighty ocean of his will that wanted to sweep away all obstacles standing as hindrances in the path of his people.

On August 16, the doctors were pleased to tell him that there was a forty percent improvement in the conditions of his lungs . Two days later he was able to begin work again, on Government Papers, for an hour a day . The word holiday was alien to his mind. Once he was asked about his Chief recreations to forget his office worries. He answered, “My profession is such that it never allows me time for recreation” . However, overwork killed him.

During these days, Mr. Mohammad Ali, Secretary of the Cabinet, had arrived from Karachi, and he thought the Quaid, mentally more alert and altogether more like his old self’.

Eid-ul-Fitr was to fall that year on 27th August, and he was busy preparing his Eid day message to the nation. The message he delivered on this occasion, turned out to be his last recorded words. In the last stages of his illness, the doctors advised him to go down to Karachi as soon as possible. But he said, “Go slow, Don’t hustle me. I do want to get up and walk about but I am not so strong as yet, Don’t think I am not keen to get out of bed and don’t apply to me the treatment which a doctor did to a women who said she could not walk.

“She was seriously ill and had been confined to bed for many months. When she recovered from her illness, the doctor told her to get up, but she said, she was too weak to do so. After about a weak, the doctor again told her to get up., but she would not get up. After that another doctor was consulted who examined with her, she must get up and walk about; but she refused to follow his advice too”.

The Quaid then paused for a few seconds, gazed at the doctors and continued, “Then another doctor came who, like you, was all for quick action. He set fire to the bed without her knowledge and this made the patient jump out of it and take to her heels”. At this the Quaid laughed and added: “Don’t do that to me” . The doctors joined in the laughter.

In the first days of September, the doctors, attending on the Quaid felt as if chances of his recovery were receding. To add to his difficulties, the altitude of Quetta was having an adverse effect on his health, as he was finding difficulty in breathing, making it necessary to frequently give him oxygen.

On the evening of September 5, 1948, the Quaid developed pneumonia . For three days he ran high temperature . Worry and despair weighed heavily on those around him, and they spent their time in anxious days and sleepless nights. His end was drawing near at a time when he knew there was so much he was expected to do for his nation. In spite of afflictions of ill-health, his mind continued to breathe burden of responsibilities of State. The problems confronting the new State were his unshakable pre-occupation, and often in his sleep he would say “Pakistan”. His Sub-conscious self revealed the innermost mumble the words, “Kashmir”, “Refugees”, “Constitution”, wished of an anxious heart . In the words of Fatima Jinnah, “in spite of his physical disabilities, his mind was active and alert, his spirit undampened and undaunted. He had won may battles in life; he faced his struggle against ill-health with confidence. He had spent all his life treading the fiery path of struggle and defiance, and he did not want to end it in the ashes of complacency. He continued to talk to me frequently about a new constitution, about Kashmir, about the refugees and I could see in his words the agony of a soul that wanted to do so much and who had so little time and strength left to do it. Nonetheless, he believed the candle should go on shedding its light until the dawn had taken over its task” . In a desperate attempt to save his life, it was decided to remove him from the altitude of Quetta to the sea-level of Karachi. Discreetly, the news was conveyed to the Quaid-i-Azam that it was essential to leave Quetta at once for Karachi.

On September 10, Dr. Bakhsh had to tell Miss Jinnah that there was little hope of her brother living for more than a few days . Next morning, three aircrafts were landed nearby, including the Quaid’s beautiful Viking, to which he was carried on a stretcher. As he was being carried on a stretcher into the cabin of the Vicking, the pilot and the crew lined up to give him a salute. He raised his feeble and trembling hand with difficulty to return the salute.

He was laid comfortably in the seats that had been converted into an improvised bed in the front cabin, and with him sat Miss Fatima Jinnah, and the nurse, sister Dunham. Within a few minutes the air craft was flying at 7000 feet, over the rugged Quetta hills… after about two hours flying, the Viking landed at Mauripur Airport at 4:15 P.M. the arrival was kept a close secret.

As instructed in advance, there was no one at the airport. Colonel Geofrey Knowles, the Military Secretary of the Governor-General, was there to receive the party. The Quaid was carried on a stretcher to a military ambulance that had been kept ready to drive him to the Governor-General’s House. Miss Fatima Jinnah and Sister Dunham sat with him in the ambulance, while the other members of the party left in cars in advance, only a Cadillac car with the doctors and the Military Secretary was following the slow moving ambulance.

After it had covered about four miles, the ambulance broke down Fatima Jinnah wrote, “After we had covered about four miles, the ambulance coughed, as if gasping for breath, and came to a sudden stop. After about five minutes, I came out of the ambulance and was told that it had run short of petrol. The driver started fidgeting with the engine, but it would not start as I entered the ambulance again, the Quaid’s hands moved slightly, and his eyes looked at me in an inquiring manner. I bent low and said to him, There is a breakdown in the engine of the ambulance.” He closed his eyes. Sister Dunham and I fanned his face by turns, waiting for another ambulance to come, every Minute an eternity of agony. He could not be shifted to the Cadillac, as it was not big enough for the stretcher. And so we waited, hoping…..

Near by stood hundreds of huts of refugees, who went about their business, not knowing that their Quaid, who had given them a homeland, was in their midst, lying helpless in an ambulance that had run out of petrol. Cars honked on their way, buses and trucks streamed to their destination, and we stood there immobilized in an ambulance that refused to move an inch, with a precious life ebbing away, drop by drop, breath by breath.

Usually there is a strong sea-breeze in Karachi, which keeps the temperature down, but that day there was no breeze, and the heat was unbearable. To add to his discomfort, scores of flies buzzed around his face and his hands had lost their strength to raise themselves to ward them off .

Sister Dunham has described the terrible hour of waiting. “We were still near enough to the refugee camp, and the mud, to be pestered by hundreds of flies I found a peace of cardboard and fanned a few minutes and he made a gesture I shall never forget. He moved his arms free of the sheet, and placed his hands on my arms. He did not speak, but there was such a look of gratitude in his eyes”.

After long and painful waiting, there came another ambulance. He was carried on the stretcher to the newly arrived ambulance and the last lap of journey began. There was no flag on the ambulance . So it moved through the city unnoticed by the crowds who had come out to enjoy the first cool breeze of evening.

At ten minutes past six in the evening the ambulance arrived at government House, and the Quaid was carried up to his room, soon to set out to his final journey. The doctors and sister Dunham tried to stimulate him with a heart tonic, but he was so weak that the medicine dribbled from the corners of his mouth.

At about 9:30 P.M. The Quaid showed signs of acute discomfort. His doctors were by his beside, examining him. His doctors raised the end of the Quaid-i-Azam’s bed, to hasten the flow of blood to his heart. Then they tried to inject a drug into his veins, but the veins had collapsed . At 9:50 Colonel Ilahi Bakhsh leaned over and whispered, “Sir, we have given you an injection to strengthen you, and it will soon have its effect. God Willing, you are going to live”.

The Quaid-i-Azam moved his head and spoke for the last time: he said faintly, “No, I am not”. Thirty minutes later, while sleeping peacefully, he breathed his last. The news of Quaid’s death spread fast and wide. There was sorrow in every heart and home throughout Pakistan. His death was felt as a personal loss for every Pakistani. It was an irreparable loss to the nascent state of Pakistan, and of the entire Muslim world. The newborn state was orphaned. The piloting light was gone when it was most needed.

He, however, was a truly great man and precious treasure. The Quaid knew what the people needed from him. He therefore, sacrificed all chances of recovery of his health and assumed the responsibility of helping the new state to overcome the initial difficulties as Governor General of Pakistan.

Notes and References

Fatima Jinnah, My Brother, edited by Sharif-Al-Mujahid, Karachi 1987 pp. 1-2.

M. Rafique, Afzal, Selected Speeches and Statements of the Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah (1911-34 and 1947-48), p. 439.

Hector Bolitho, Jinnah the Creator of Pakistan, London 1964. 214.

Ian Stephens, Pakistan an old country and new nation, London 1967 p. 50.

G. Allana, Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah The story of a Nation. Karachi 1967, p. 22.

Mir Laik Ali, Tragedy of Hyderabad, Karachi, 1967, p. 258.

Nazir Ahmad Sheikh, Quaid-i-Azam Father of the Nation, Lahroe 1968, p. 118.

Hector Bolitho, op.cit., p. 219.

Hector Bolitho, op. cit., p. 219.

Hector Bolitho, op.cit., p.220.

Ian Stephens, op.cit., p. 231.

Hector Bolitho, op.cit., p. 222.

Hector Bolitho, op.cit., p. 222.

Hector Bolitho, op.cit, p. 223.

Hector Bolitho, op.cit., p. 223.

Fatima Jinnah, op.cit., p. 223.

Hector Bolitho, op.cit., p.223.

Fatima Jinnah, op.cit., P. 224.

Hector Bolitho, op.cit., p. 224.