|

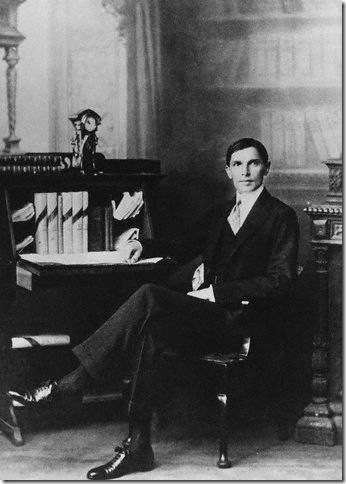

| Click on the image to enlarge |

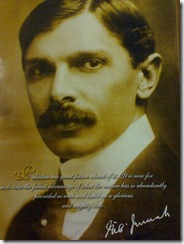

Obituary - The Times

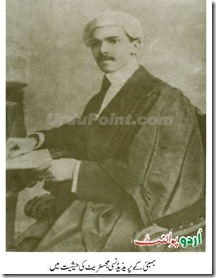

Mr. Jinnah before the Joint Select Committee

In 1911 the Joint Select Committee of the Parliament in London asked Mr. Jinnah the question:

“How do you justify an advance in self-government with a literacy percentage of only 12?”

Mr. Jinnah replied:

“Did the lack of literacy prevent you from going ahead with your successive Reforms Acts which continuously enlarged the franchise? And if it is good for England why should it be bad for India?”

.

.

Quaid-e-Azam and the Muslim World

By S. Razi Wasti

Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah became Governor General of Pakistan on 14 August 1947, but he had worked for the betterment of the Muslim world throughout his political life. In order to understand his views and policy about the Muslim world, a reference to the policy of Muslim India, before the birth of Pakistan, would be pertinent.

Many Muslims believed that India, became dar-ul-harb, after the Battle Plassey in 1757. According to them it was obvious that the British now possessed power to interfere with the religious observances of their Muslim subjects. It was, therefore, incumbent upon them to wage a holy war (Jihad) against the British to reconvert the country into dar-ul-Islam. Another school represented by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan declared that Jihad against the British was not desirable for the reasons that Muslims enjoyed peace and religious freedom under the British rule.

It was the former conception that provided the inspiration for the Mujahideen Movement, which was the first significant effort aimed at expelling the British from India. Syed Ahmed Barelvi died on the battlefield at Balakot in 1831 but he left behind a well established organisation and his followers stubbornly continued the fight. The War of Independence (1857) was also fought under a Muslim flag. Far from restoring the full power of the Mughal Emperor, the rising of 1857 resulted in his banishment and the complete British sovereignty over India. Until the close of the nineteenth century the Muslims of the Indo-Pakistan subcontinent evinced no keen interest in the politics of India.

At the opening of the twentieth century events outside India added to the concern of the Muslims. During Russo-Turkish War of 1877 the Indian Muslims for the first time demonstrated their sympathy for the Turks on a wider scale. All Turkish causes i.e. the 1897 war with Greece, the 1911 war with Italy and Balken War of 1912 evoked agitation in India. The situation became still more difficult when a few months after the outbreak of World War in 1914, it ended in Turkey’s defeat.

The British Foreign Policy towards Muslims States, especially Turkey, continued to add to anxieties of Indian Muslims. In 1907 British signed a Convention with Russia – the traditional enemy of Turkey. This greatly threatened the Independence of Iran as well. In 1911 Italy attacked and occupied Tripoli. Consequently, war broke out between Italy and Turkey. The war expanded, and in October 1912, the Balkan States also declared war on Turkey. As a result almost all of her European possessions except Thrace, Constantinople and the Straits, were lost to Turkey. These developments soon attracted the attention of the Indian Muslims. The Sultan of Turkey “was the Khalifa or Successor of the Prophet and Amir-ul-Momineen or Chief of the Faithful”.1 The plight of Turkey naturally caused tremendous amount of anxiety to the Indian Muslims. The news of inhuman atrocities perpetrated on the innocent Turks irrespective of sex or age by the Italians, the conquest and desecration fo the Holy Places of Islam, the French occupation of Morocco and the Russian hangings of Meshhad ‘ulama, deeply grieved the Indian Muslims. They attributed all those sufferings to Europens, especially the British, who in their opinion were out to destroy Islam everywhere in the world.2 A fire seemed to have swept over the entire country. Orators of great repute like Shaukat Ali, Muhammad Ali, Abul Kalam Azad and Shibli Nu’mani condemned in unequivocal terms the brutalities perpetrated on the Turks by the aggressors. They also severely denounced the British Government for the support it was lending to the belligerents. A number of papers critical of the British Imperial policy and in favour of the Pan-Islamic Movement began to appear. The most popular and vocal among these were the al-Hilal started by Abul Kalam Azad from Calcutta, Muhammad Ali’s Comrade and Hamdard and Zafar Ali Khan’s Zamindar. The Aga Khan and Syed Ameer Ali, Presidents of the All India Muslim League and the London Branch of the League respectively, conducted a similar campaign in favour of the Turkish brethren. They made earnest appeals to the British Government and public to effect that every possible effort be made to save Turkey from total disintegration. They also appealed to the Indian Muslims to sacrifice their all for the support of the wounded, sick and starving Turks, to form national help-committees, to pray for the success of the Turks and contribute Hilal-i-Ahmar Fund3.

The British Foreign Policy towards Muslims States, especially Turkey, continued to add to anxieties of Indian Muslims. In 1907 British signed a Convention with Russia – the traditional enemy of Turkey. This greatly threatened the Independence of Iran as well. In 1911 Italy attacked and occupied Tripoli. Consequently, war broke out between Italy and Turkey. The war expanded, and in October 1912, the Balkan States also declared war on Turkey. As a result almost all of her European possessions except Thrace, Constantinople and the Straits, were lost to Turkey. These developments soon attracted the attention of the Indian Muslims. The Sultan of Turkey “was the Khalifa or Successor of the Prophet and Amir-ul-Momineen or Chief of the Faithful”.1 The plight of Turkey naturally caused tremendous amount of anxiety to the Indian Muslims. The news of inhuman atrocities perpetrated on the innocent Turks irrespective of sex or age by the Italians, the conquest and desecration fo the Holy Places of Islam, the French occupation of Morocco and the Russian hangings of Meshhad ‘ulama, deeply grieved the Indian Muslims. They attributed all those sufferings to Europens, especially the British, who in their opinion were out to destroy Islam everywhere in the world.2 A fire seemed to have swept over the entire country. Orators of great repute like Shaukat Ali, Muhammad Ali, Abul Kalam Azad and Shibli Nu’mani condemned in unequivocal terms the brutalities perpetrated on the Turks by the aggressors. They also severely denounced the British Government for the support it was lending to the belligerents. A number of papers critical of the British Imperial policy and in favour of the Pan-Islamic Movement began to appear. The most popular and vocal among these were the al-Hilal started by Abul Kalam Azad from Calcutta, Muhammad Ali’s Comrade and Hamdard and Zafar Ali Khan’s Zamindar. The Aga Khan and Syed Ameer Ali, Presidents of the All India Muslim League and the London Branch of the League respectively, conducted a similar campaign in favour of the Turkish brethren. They made earnest appeals to the British Government and public to effect that every possible effort be made to save Turkey from total disintegration. They also appealed to the Indian Muslims to sacrifice their all for the support of the wounded, sick and starving Turks, to form national help-committees, to pray for the success of the Turks and contribute Hilal-i-Ahmar Fund3.

The cumulative effect of all these campaigns was that huge funds were raised for the support of the Turks; branches of the Red Crescent were formed throughout the country; a Medical Mission was organized and dispatched to the scene of War under the leadership of Dr Mukhtar Ahmad Ansari. An association under the name of Anjuman-i-Khuddam-i-Ka’bah was formed by Mushir Hussain Qidwai in collaboration with Shaukat Ali and others. The association was to unite the Musalmans of every section maintaining in violate the sanctity of the three Harams of Islam at Mecca, Medina and Jerusalem.4 These were the beginnings of the Khilafat Movement which was to acquire unprecedented dimensions after World War I.

Ever since the change in British policy, the maintenance of the territorial integrity and independence of the Ottoman Empire had become the primary concern of the Indian Muslims. They apprehended that if Turkey too lost her independence, then the Muslims, like the Jews, would be reduced to a mere religious sect without any Government of their own.

The Muslims of India were deeply anxious that after the war the status of the Sultan both territorial and spiritual should remain undisturbed. Between 1912 when the first Balkan war began and 1922 when Turkey made peace with the European powers the Indian Muslims were completely absorbed in the fate of Turkey and Arabia.

With the abolition of the Khilafat, the Muslims of India lost the overseas rallying point for Muslim resurgence and increasingly began to feel that, as the most substantial body of believers in the world, it was more incumbent upon themselves than upon others to strive for the solidarity of Islam.

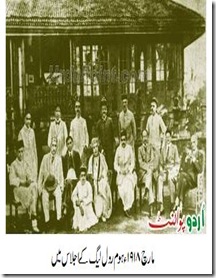

The Muslim League had been founded in 1906, but for many years it remained comparatively a small conservative organization, consisting of mainly upper class professionals and landed Muslims. It was not very active during the Khilafat Movement. On 24-25 May, 1924 the League met at Lahore under the Presidentship of Quaid-i-Azam. In 1925 suspecting that Iraq was about to be handed over the Britain as a mandatory power, the League passed a resolution, declaring that Iraq was a part of Jazirat ul Arab and as such should not be left under the control of a non-Muslim mandatory power. The League protested against the Mosul decision of Council of the League of Nations as a glaring injustice to Turkey and hoped that Britain would recognize the right of Turkey to the Mosul Vilayat and settle the question by peaceful negotiation.5 At the Delhi session in November 1933 the League placed on record its emphatic protest against the policy of the British Government in trying to make Palestine the national home of the Jews. The Muslim League depicted the views of Muslims India over matter concerned with Muslims outside India.6

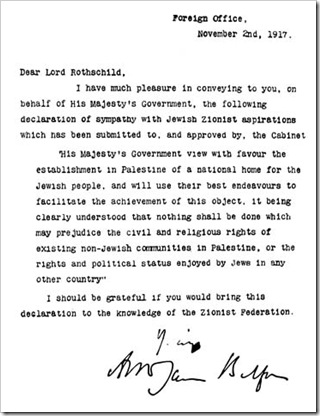

Quaid-i-Azam was elected as the permanent President of the Muslim League in 1934. He was now able to direct the League’s action within and without the country according to his genius. In 1937 in his Presidential address he stated, “May I now turn and refer to the question of Palestine? It has moved the Musalmans all over India most deeply. The whole policy of the British Government has been a betrayal of the Arabs, from its very inception. Fullest advantage has been taken of their trusting nature. Great Britain has dishonoured her proclamation to the Arabs, which had guaranteed them complete independence for the Arab homelands, and the formation of an Arab Confederation under the stress of the Great War. After having utilized them, by giving them false promises, they installed themselves as the Mandatory Power with that in famous Balfour Declaration, which was obviously irreconcilable and incapable of simultaneous execution. Then, having pursued the policy to find a national home for the Jews, Great Britain now proposes to partition Palestine, and the Royal Commission’s recommendation completes the tragedy. If given effect to , it must necessarily lead to the complete ruination and destruction of every legitimate aspiration of the Arabs in their homeland – and now we are asked to look at the realities: But who created this situation? It has been the handiwork of, and brought about sedulously by, the British statesmen. The League of Nations has, it seems, and let us hope, not approved of the Royal Commissions’ scheme, and a fresh examination may take place. But is it a real effort intended to give the Arabs their due? May I point out to Great Britian that this question of Palestine, if not fairly and squarely met, boldly and courageously decided, is going to be the turning point in the history of the British Empire. I am sure I am speaking not only the Musalmans of India but of the world, and all sections of thinking and fair-minded people will agree, when I say that Great Britain will be digging its grave if she fails to honour her original proclamation, premises and intentions – pre-war and even post-war – which were so unequivocally expressed to the Arabs and the world at large. I find that a very tense feeling of excitement has been created and the British Government, out of sheer desperation are resorting to repressive measures, and ruthlessly dealing with the public opinion of the Arabs in Palestine. The Muslims of India will stand solidly and will help the Arabs in every way they can in the brave and just struggle that they are carrying on against all odds. May I send them a message on behalf of the All India Muslim League – of cheer, courage and determination in their just cause and struggle, and that I am sure they will win through?”7

Quaid-i-Azam was elected as the permanent President of the Muslim League in 1934. He was now able to direct the League’s action within and without the country according to his genius. In 1937 in his Presidential address he stated, “May I now turn and refer to the question of Palestine? It has moved the Musalmans all over India most deeply. The whole policy of the British Government has been a betrayal of the Arabs, from its very inception. Fullest advantage has been taken of their trusting nature. Great Britain has dishonoured her proclamation to the Arabs, which had guaranteed them complete independence for the Arab homelands, and the formation of an Arab Confederation under the stress of the Great War. After having utilized them, by giving them false promises, they installed themselves as the Mandatory Power with that in famous Balfour Declaration, which was obviously irreconcilable and incapable of simultaneous execution. Then, having pursued the policy to find a national home for the Jews, Great Britain now proposes to partition Palestine, and the Royal Commission’s recommendation completes the tragedy. If given effect to , it must necessarily lead to the complete ruination and destruction of every legitimate aspiration of the Arabs in their homeland – and now we are asked to look at the realities: But who created this situation? It has been the handiwork of, and brought about sedulously by, the British statesmen. The League of Nations has, it seems, and let us hope, not approved of the Royal Commissions’ scheme, and a fresh examination may take place. But is it a real effort intended to give the Arabs their due? May I point out to Great Britian that this question of Palestine, if not fairly and squarely met, boldly and courageously decided, is going to be the turning point in the history of the British Empire. I am sure I am speaking not only the Musalmans of India but of the world, and all sections of thinking and fair-minded people will agree, when I say that Great Britain will be digging its grave if she fails to honour her original proclamation, premises and intentions – pre-war and even post-war – which were so unequivocally expressed to the Arabs and the world at large. I find that a very tense feeling of excitement has been created and the British Government, out of sheer desperation are resorting to repressive measures, and ruthlessly dealing with the public opinion of the Arabs in Palestine. The Muslims of India will stand solidly and will help the Arabs in every way they can in the brave and just struggle that they are carrying on against all odds. May I send them a message on behalf of the All India Muslim League – of cheer, courage and determination in their just cause and struggle, and that I am sure they will win through?”7

In 1937 the League passed five resolutions and demanded the annulment of the British mandate in Palestine and warned the British Government that if it failed to alter its pro-Jewish policy in Palestine ‘the Mussalmans of India in consonance with the rest of the Islamic world will look upon the British as the enemy of Islam and shall be forced to adopt all necessary measures according to the dictates of their faith’.8

Again in his presidential address to the 26th session of the League held at Patna in December 1938, the Quaid stated, “Among the immediate issues we have to grapple with, which may come upon before the Subjects Committee, is the question of Palestine. I know how deeply Muslim feelings have been stirred over the issue of Palestine. I know Muslims will not shirk from any sacrifice if required to help the Arabs who are engaged in the fight for their national freedom. You know the Arabs have been treated shamelessly – men who, fighting for the freedom of their country, have been described as gangsters, and subjected to all forms of repression. For defending their home-lands, they are being put down at the point of the bayonet, and with the help of martial laws. But no nation, no people who are worth living as a nation, can achieve anything great without making great sacrifices, such as the Arabs of Palestine are making. All our sympathies are with those valiant martyrs who are fighting the battle of freedom against usurpers. They are being subjected to monstrous injustices which are being propped up by British Imperialism with the ulterior motive of placating the international jewry which commands the money bags. That question we will have to consider.”9

The League called for observance of ‘Palestine Day’, holding of protest meetings and for the offering of prayers.10 A deputation consisting of four leaders was sent abroad to promote the Arab cause. It remained overseas for nine months visiting Cairo, London, Geneva, Rome and Bairut.

In December 1938 the Muslim League passed a resolution that “the unjust Balfour Declaration and the subsequent policy of repression adopted by the British Government in Palestine aim at making their sympathy for the Jews a pretext for incorporating that country into the British Empire with a view to strengthen British Imperialism and to frustrate the idea of Federation of Arab States and its possible Union with the Muslim States”.11 Next year in 1939 the Palestine Fund was opened.

After the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, the League Council “resolved that in view of the repeated reports that have reached India recently that there is a probability of war flames spreading and aggression by foreign powers against the independence and sovereignty of the Muslim countries such as Egypt, Palestine, Syria and Turkey, the President is hereby authorized to fix a day for the purpose of expressing and demonstrating deep sympathy and concern of Muslim India with Muslim countries and also conveying to those who have any such design that in the event of an attack upon Muslim countries, Muslim India will be forced to stand by them and give all the support it can.”

In the course of his Presidential address at the historic Lahore session of the League in March, 1940, Quaid-i-Azam said that the Muslim wanted “that the British Government should in fact and actually meet the demands of the Arabs in Palestine”.12 It urged the British Government and its allies to declare unequivocally that the sovereignty and independence of those Muslim States would be restored as soon as circumstances permitted.

Addressing the Aligarh Muslim University Union on 9 March, 1944, Quaid-i-Azam warned that “if President Roosevelt, under the pressure of the powerful World Jewry, commits the blunder of forcing the British Government to do injustice to the Arabs in Palestine, this would set the whole Muslim World ablaze from one end to another”. He hoped that “the U.S. will revise their attitude toward Palestine.”13

In December, 1943, the League urged Britain and allied powers not to hand back to the Italian Government the territories recently released from the control of Italy namely Cyreneca, Libya and Tripoli but to constitute them as independent sovereign states. At the same time League demanded the abolition of the vicious system of mandates and the restoration of Palestine, Syria and Lebanon to the peoples of those countries and to enable them to set up their own sovereign governments. Finally in the same resolution the League demanded that the Allied powers press France to liberate Morocco, Algeria and Tunis.14 When the Netherlands landed fresh troops in Indonesia, the League in April 1946 resolution noted with regret that the right of the Indonesian people to independence had not been recognized, condemned delay in the withdrawal of British troops from Indonesia and sent a message of greetings and congratulation to the Indonesian people for their struggle for freedom against heavy odds and assured them of their sincerest sympathy and support of the Muslim nation of India for their just and patriotic cause.”15

In 1945 in a telegram to Prime Minister Attlee, the Quaid said, “President Truman’s reported Palestine immigration proposal is unwarranted, encroaching upon another country, monstrous and highly unjust. Any departure from the White Paper and Britain’s pledge will not only be a sacrilege and a breach of faith with Muslim India but an acid test of British honour. It is my duty to inform you that any surrender to appease Jewry at the sacrifice of Arabs would be deeply resented and vehemently resisted by Muslim world and Muslim India and its consequences will be most disastrous.”16

In a speech at a meeting held under the auspices of Baluchistan Muslim League at Quetta, on 10 October 195, the Quaid talked about the Palestine affairs and Indonesian struggle for freedom and said, “Jews are also suffering from the same disease as the Congress. Over half a million Jews have already been accommodated in Jerusalem gainst the wishes of the people. May I know which other country has accommodated them? I have great sympathy for them and have no ill-will against the Jews but the question is that they have entered Palestine with a set motive to reconquer Jerusalem (which they lost 2,000 years ago) with the help of British and American forces. I hope the Jews will not succeed in their nefarious designs and I wish Great Britain and America should keep their hands off from them, and then I will see how the Jews conquer Jerusalem. Every man and the women of Muslim world will die before Jewry seizes Jerusalem. Slave and a subject race as we are, still our hearts and souls go in sympathy with those who are struggling for their freedom and let us hope that the people of Palestine and Indonesia will survive their ordeals. Subjugation and exploitation, if carried now, there will be no peace and end of wars. And if such exploitation of small nations is to continue even after this bloody war then let us pray to God to send some more destructive force than the atomic bomb to do the work and job of this world.”17

Muslim causes other than the Palestine question equally evoked the League’s solicitude under the guidance and the Quaid. The Muslim League characterized the war time occupation of Iran by British and Soviet troops as “unprovoked aggression”, which would “alienate the sympathies of the Muslims of India and create bitterness in their hearts resulting in the withdrawal of every help by them to the Allied cause.” (1941)

In August 1947 the new State of Pakistan emerged on the map of the world. Now the Muslims of this State were to have foreign policy of their own. A country’s foreign policy is subservient to a number of factors. It is dependent, to a considerable extent, upon its defence requirements, history and geographical location, ideological consideration and exigencies of moment sway its orientation. There are only permanent interest in foreign affairs and no permanent friends. A country’s relation with others nations at a particular time reflect its economic and strategic needs. The results of a particular policy depend upon a country’s own importance in world affairs. Its size, economic strength, strategic position, industrial potentialities and of late its scientific achievements, all determine the weight it can exert to tip the scales.

Facts of the geography cannot be altered. They have to be accepted along with all permanents problems they raise. Geographical facts are great ingredients in shaping the habits and character of the people and the foreign policy of a nation is greatly moulded by its geographical environment. Pakistan at the time of Partition had a unique geographical position. It consisted of two wings separated from each other by Indian territory about a thousand miles. It had a common front of two thousand miles with India. West Pakistan consisted of West Punjab, North West Frontier Province, Baluchistan, Sind and the small States of Bahawalpur, Khairpur, Chitral, Kalat, Las Bela, Swat, Dir and some minor ones. West Pakistan was bordered on the East by India on the West by Afghanisstan and Iran, on the north China, and territory less than a score of miles with Russia and Kashmir, on its south lay the Arabian Sea. East Pakistan comprised of East Bengal and the fertile district of former Assam, it was bordered on the East, West and North by India with the Bay of Bengal in its South. Such a queer geographical position affected the foreign policy of Pakistan.

Besides economic and defence consideration, there is another fundamental principle which had influenced Pakistan largely in the determination of her foreign policy, that is her Muslim ideology. The very foundation of our country is based upon Islamic Ideology. Muslims of undivided India were determined to have a separate sovereign State of their own where they might be able to order their lives according to the tenets of Islam and could preserve their safety and tranquility, their religion, their culture, their way of life, and could ensure the advancement of their people. It were their ideological feelings which made mullions of Muslims in India to leave their homes and migrate to Pakistan.

During her early months Pakistan ‘s foreign policy amounted to little more than the will of her leaders and people that she should survive, Quaid-i-Azam’s statements about it were studiously platitudinous. Goodwill was professed for all countries, belief in international honesty and fair play, readiness to contribute towards peace and so on. Nevertheless certain learnings or attitude as contrasted with solid formulations of policy soon became discernible. One was warmth for Muslim countries.

Quaid-i-Azam expressing his views on Pakistan’s foreign policy said, “As a new born State, Pakistan desires nothing so ardently as the goodwill of the world. Its people are determined to work with heart and soul in the task consolidating their new liberty and while so engaged in this great task they will be deeply conscious of the help and co-operation extended to them by the other States of the world, particularly at this moment.”18

Quaid-i-Azam wanted to establish a strong and affective bloc consisting of all Muslim States of the world, to see that they were united with the banner of Islam as an efficient bulwark against the aggressive and evil design of their enemies. He vehemently opposed the Partition of Palestine and condemned the establishment of Israel as a dagger in the heart of the Arab world. He said “I do still hope that Partition plan will be rejected, otherwise there is bound to be the gravest disaster and unprecedented conflict….The entire Muslim World will revolt against such a decision…Pakistan will have no other course left but to give its fullest support to the Arabs and will do whatever lies in its power to prevent what in my opinion is an outrage.”

Quaid-i-Azam wanted to establish a strong and affective bloc consisting of all Muslim States of the world, to see that they were united with the banner of Islam as an efficient bulwark against the aggressive and evil design of their enemies. He vehemently opposed the Partition of Palestine and condemned the establishment of Israel as a dagger in the heart of the Arab world. He said “I do still hope that Partition plan will be rejected, otherwise there is bound to be the gravest disaster and unprecedented conflict….The entire Muslim World will revolt against such a decision…Pakistan will have no other course left but to give its fullest support to the Arabs and will do whatever lies in its power to prevent what in my opinion is an outrage.”

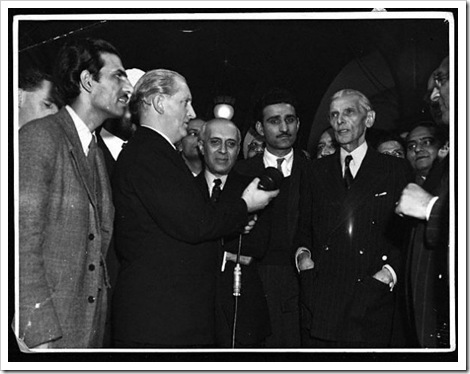

In an interview to Mr. Robert Stimson, B.B.C. correspondent on 19 December 1947, the Quaid said, “…our sense of justice obliges us to help the Arab cause in Palestine in every way that is open to us.”19 He expressed feelings of thanks in his telegram on December 24, 1947 to the King of Yemen, Imam Yahya in reply to his telegram of thanks for Pakistan’s support to Arabs on Palestine issue. He stated, “I once more assure you and our Arab brethren that Pakistan will stand by them and do all that is possible to help and support them in their opposition on the U.N.O. decision which is inherently unjust outrageous.”20

In reply to the speech by Muhammad Pasha el Shuraiki, Jordonian Minister Plenipotentary, the Quaid emphatically stated “Islam is to us the source of our very life and existence and it has linked our cultural and traditional past so closely with the Arab world that there need to be doubt whatsoever about our fullest sympathy for the Arab cause.”21

In an Eid message Quaid-i-Azam said “My Eid message to our brethren Muslim States is one of friendship and goodwill. We are all passing through perillous times. The drama of power politics that is being staged in Palestine, India and Kashmir should serve an eye opener to us. It is only by putting up a United Front that we can make our voice felt in the Councils of the world.”22

Quaid-i-Azam gave open support to North African Arabs in their struggle to throw off the Fench yoke. He considered the Dutch attack upon Indonesia as an attack on Pakistan itself and refused transit facilities to Dutch ships and place, carrying war materials to Indonesia. He played an important role in the struggle of Muslim countries. He, therefore, provided all possible diplomatic and material assistance to the liberation movement in Indonesia, Malaya, Sudan, Libya, Tunisia, Morocco, Nigeria and Algeria.

Pakistan’s relation with brotherly Muslim States of Jordan, specially Turkey and Iran, were most cordial and friendly. They contributed to the Quaid-i-Azam’s Relief Fund and exchanged missions and diplomatic representatives.

Thus under the leadership of Quaid-i-Azam, Pakistan took an active part to bring Muslim world together.

S. Razi Wasti is the Professor and Head, Department of History, Dean, Faculty of Arts, Government College, Lahore.

References

- Muhammad Ali, My Life: A Fragment, edited by Afzal Iqbal, Lahore, 1946, P. 57.

- See Vakil, Amritsar, 8 November 1911, Punjab Native Newspaper Reports, 25 November 1911, P. 1177; also Al-Hilal, Calcutta, 26 February 1913.

- Ameer Ali’s telegram to the daily Paisa Akhbar, Lahore, dated 22 October, published on 29 October, 1912.

- Muhammad Ali, op. cit., P. 67; see also al-Hilal Calcutta, 20 May, p. 67.

- Syed Sharif-uddin Pirzada; Foundations of Pakistan Vol II, 1970, p. 71.

- Ibid., P. 223, See Presidential address and pp. 225 and 226 Resolution, No. VII.

- Ibid., P. 272.

- Ibid., P. 278.

- Ibid., P. 307.

- Ibid., PP. 315-317.

- Ibid., P. 315.

- Jamil uddin Ahmad, Speeches and Writing of Mr. Jinnah, Lahore, 1960, vol. I, PP. 154-155.

- Ibid., 1964, Vol. II, P. 14.

- S.S. Pirzada, Op. cit., Vol. II, PP. 479-480.

- Ibid., PP. 525-527.

- Ibid., Vol. II. P. 214.

- Ibid., 1964 Vol. II, PP. 220-221.

- Reply to the speech made by the Afghan Ambassador at the time of presenting his credentials on 8 May 1948. Jamil uddin Ahmad, Vol. II, op. cit., PP. 554-555.

- M. Rafique Afzal – Selected Speeches and Statesman of the Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Lahore 1966, P. 452.

- Ibid., P. 453.

- Ibid., P. 454.

- Message to the Nation on the occasion of Eidul Fitar, August 27, 1948, Jamil uddin Ahmad, op. cit., Vol. II, p. 569.

Source: World Scholars on Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Edited by: Ahmad Hasan Dani, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan 1979.

Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah as a Parliamentarian

By Mukhtar Zaman

Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah had many qualities, but he tops the list in three of them; as a lawyer, as a parliamentarian and as a public leader. As a public leader, with odds against him, he performed the political miracle of this century by founding an independent country. In all the three his mental powers, oratory, determination, honesty and straightforwardness help him. But, here, let us confine to discuss only one of his achievements i.e., as a parliamentarian.

Mr. Jinnah was still in London studying law when he was attracted by politics. Politics often leads to Parliament and law helps both of them. He attended the British Parliament regularly and attentively watched from gallery, the ways, manners, gestures and even the dress of prominent honourables members. Men like Gladstone, T.P. Connor, Joseph Chamberlain formed a lasting impression on his mind.

Hector Bolitho has pointed out that his reader’s tickets of the British Museum still exists in the British metropolis. Apparently, besides other books, he read all the significant speeches of important parliamentarians at the British Museum. Naturally this formed the background of his parliamentary career. Bolitho has also quoted Dr. Ashraf as saying that the Quaid-i-Azam used to meet the liberal leaders of Britain very often. It is well known that the Quaid himself leaned towards liberalism. He was not a sectarian narrow-minded and intolerant politician. In his parliamentary career he always stood for liberal policies. He demanded, as in Ireland, a separate homeland for Muslims, when he said that the Congress party has deviated from its liberal policy and had entered narrow grooves of partisanship. He listened in 1893 to the “lively debate” over Gladstone’s Irish Home Rule Bill. Even at that time he stood firmly for the self-determination of the Irish people. In fact the British Parliament, inspite of his differences with its policies, seems to have played an instructive role in the formation of his character. Somewhat at the back of his mind future membership of Indian Parliament, and the manners and rules that he was likely to use may have been natural. Some think that the use of monocle was also a reminder of his fondness for parliament. After completing his education in England, and being called to bar as the youngest Indian barrister he returned to India in 1896 to start practice.

Dr. Mohammad Umar says that Mr. Jinnah started his Parliamentary career with his election to the Imperial Legislative Council in 1909. He remained its member till March 28, 1919. But he resigned as a protest against what is known as the Rowlatt Act, after the name of Mr. Justice Rowlatt who presided over an official Committee to “detain and try” insurgents and achieve enemies of its policy. Mr. Jinnah speaking on the Bill vehemently opposed it as a “new shackle on the freedom of the people.” He “enumerated his objections on his fingers” in the Legislative Council, and said:

….It is my duty to tell you that if these measures are passed they will create in this country from one end to the other a discontent and agitation the like of which you have not witnessed, and it will have, believe me, a most disastrous effect upon the good relations that have existed between the Government and the people.

But inspite of his protest the Rowlatt Bill was passed because Government members formed a majority. On March 28 Mr. Jinnah wrote to the Viceroy that the Government of India had “ruthlessly trampled upon the principles” for which Great Britain avowedly fought a war. He added that the Imperial Legislative Council was “a legislature but in name a machine propelled by foreign executives”.

As a protest against the Rowaltt Act he tendered his resignation. He hoped in the end that this black Act would be annulled.

It should be noted that while Jinnah resigned, men like Motilal Nehru continued to sit comfortably in their chairs.

When the Central Legislative Assembly came into being he was again elected from a Bombay Urban constituency in November 14, 1923. He remained in England from October 1930 to December 1934. In October 1934 he was re-elected to the Assembly. When Pakistan came into being he was elected as Chairman of the National Assembly – a post that he held till his death.

In 1910 when he was a member of the Viceroy’s Council the British ruled the roost. The British empire spread far and wide. The Viceroy was almost like a Moghal King. But Jinnah was undaunted as ever. He clashed with the Viceroy Lord Minto on the question of South Africa. He called for an immediate end to send the indentured labour to South Africa. On February 25 Jinnah, while speaking in the house, said: “It is most painful question – a question which has aroused the feelings of all classes in the country to the highest pitch of indignation and horror at the harsh and cruel treatment meted out to Indians in South Africa.”

Lord Minto could not tolerate such words. He objected to the phrase cruel treatment which, he said was “too harsh to be used for a friendly part of the empire.”

To this remarks Jinnah replied:

I should feel inclined to use much stronger language. But I am fully aware of the constitution of this Council and I don’t wish to trespass it for one single moment. But I do say that treatment meted out to Indians is the harshest and the feeling in this country is unanimous.

Wolpert writes “that brief exchange reflected Jinnah’s courtroom as well as Council style. He always chose his words carefully and never retraced any, once uttered. His critics, whether Judges, Viceroys or Pandits, usually received humiliating tongue lashings for any barly aimed at him. He was not known to sit silent for the slightest reprimand having his razor sharp mind and words on and generally duller weapons of logic or wit drawn against him. Lord Minto appalled at Jinnah’s response was struck dumb by it. Jinnah, “the Muslims member from Bombay”, sat in the Council chamber, built by Lord Wellesley, in a distinguished company as it consisted men like Gopal Krisna Gokhale, Motilal Nehru, Surendra Nath Banerji and poor Minto vainly hoped for support of this enlarged Council.”

Wolpert writes “that brief exchange reflected Jinnah’s courtroom as well as Council style. He always chose his words carefully and never retraced any, once uttered. His critics, whether Judges, Viceroys or Pandits, usually received humiliating tongue lashings for any barly aimed at him. He was not known to sit silent for the slightest reprimand having his razor sharp mind and words on and generally duller weapons of logic or wit drawn against him. Lord Minto appalled at Jinnah’s response was struck dumb by it. Jinnah, “the Muslims member from Bombay”, sat in the Council chamber, built by Lord Wellesley, in a distinguished company as it consisted men like Gopal Krisna Gokhale, Motilal Nehru, Surendra Nath Banerji and poor Minto vainly hoped for support of this enlarged Council.”

In 1926 the urban constituency selected him to the Indian Legislative Council. He attached himself to the “independent” group and became its leader. At that time the British Parliament sent Sir John Simon to find out the public opinion in India. But it is a sad fact that the Simon Commission did not consist of a single Indian member. Jinnah and other Indian leaders boycotted the Commission with the slogan “Go back Simon”. At Lucknow, and Bombay etc. Simon faced stiff opposition. This also indicates the Jinnah was never prepared to tolerate even parliamentary action which he thought unwarranted and wrong.

When Gopal Krishna Gokhale in 1912 moved the primary education Bill, he found full backing from Jinnah, who always supported the education of boys and girls alike. According to “Quaid-i-Azam and Education” published by the Karachi Board of Intermediate Education while speaking in the Legislature he said,”…..we are convinced that there is no salvation for masses unless the principle of compulsion (compulsory education) is introduced in this country.”

Mr. Jinnah congratulated Mr. Gokhale for the “able and masterly way” in which he dealt with the question. He said, “it will take 175 years in order to get all school-going children to scool and 600 years to get all the girls to school.”

In this situation he wanted more vigorous steps in educating the people. He also replied to critics who said that “if the common population is educated they will become “too big for their boots”, and “will demand more rights”. He asked: “Are you going to keep millions and millions of people trodden under your feet to fear that they may demand more rights, are you going to keep them in ignorance and darkness for ever and in all ages to come because they may stand up against you and say that “we have certain rights and you must give them to us.” He declared that he had no hesitation in supporting the Bill.

Another masterpiece of Mr. Jinnah is Waqf Validating Bill (1911). The text of Bill has been reproduced by Sharif al Mujahid in Jinnah: Studies in interpretation (P. 453). The statement of objects and reasons says that the Bill aimed at removing the “hardship” that had been created by certain decisions of Privy Council. These decisions paralysed “the power of a Mussalman to make a settlement for/in favour of his family, children and descendants or what is known as Waqf Alal Aulad. The Bill intended to reproduce the Muslim law of Waqf Alal Aulad in a codified form with certain safeguards for the authenticity of waqfnama and for prevention of fraud upon creditors or otherwise. Known as Mussalman Wakf Validating Act 1913, it received the assent of the Governor General on 7th March, 1913.

Dr. Mohammad Umar while analyzing Quaid-i-Azam’s parliamentary career has enumerated several of his qualities. They are his strategy, keen insight, able advocacy, clear representation, reasoning power, balanced judgement and undaunted criticism. He says that Quaid was very often witty and sarcastic which distinguished him as a parliamentarian. Keeping all these qualities in view the author concludes that the Quaid was “a born parliamentarian”. His self-confidence, sincerity, honesty, outspokenness and frankness coupled with his ability and acumen made him ideal in his parliamentary career.”

Dr. Mohammad Umar while analyzing Quaid-i-Azam’s parliamentary career has enumerated several of his qualities. They are his strategy, keen insight, able advocacy, clear representation, reasoning power, balanced judgement and undaunted criticism. He says that Quaid was very often witty and sarcastic which distinguished him as a parliamentarian. Keeping all these qualities in view the author concludes that the Quaid was “a born parliamentarian”. His self-confidence, sincerity, honesty, outspokenness and frankness coupled with his ability and acumen made him ideal in his parliamentary career.”

K. Ali Afzal, an official of the Federal Assembly, says the Quaid had “great respect” for “parliamentary traditions”.

In the collection of essays on Quaid-i-Azam by Professor Ziauddin, he says that the speaker of an Assembly is like an umpire in a game, who must be impartial.

The Quaid-i-Azam as Governor General was the head of the executive and his presidentship would have taken the tradition to pre-1919 days. Therefore the Quaid-i-Azam presided over the meetings of the Assembly when it met as a constitution making body but Maulvi Tamizuddin Khan presided when it met as a Legislature. What a happy and progressive arrangement and a tribute to the political genius of the Quaid-i-Azam.

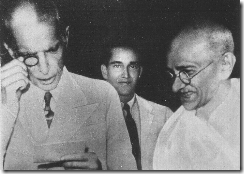

It was the Assembly which on August 12, 1947 formally conferred on him the title of Quaid-i-Azam on Mohammad Ali Jinnah. Ali Afzal says as soon as the Quaid took the Chair his first action was to put on his monocle and read the agenda. “After he had read the agenda, the monocle would drop down by the …. of the muscles of the eye-brow. His monocle became a part of his personality and suited the aristocratic features admirably”. When Quaid died according to Ali Afzal, Maulana Shabbir Ahmad Usmani had dreamt about the same time that a great rock had rolled down.

It was the Assembly which on August 12, 1947 formally conferred on him the title of Quaid-i-Azam on Mohammad Ali Jinnah. Ali Afzal says as soon as the Quaid took the Chair his first action was to put on his monocle and read the agenda. “After he had read the agenda, the monocle would drop down by the …. of the muscles of the eye-brow. His monocle became a part of his personality and suited the aristocratic features admirably”. When Quaid died according to Ali Afzal, Maulana Shabbir Ahmad Usmani had dreamt about the same time that a great rock had rolled down.

It should be recalled that on the issue of Waqfs, he consulted Maulana Shibli Nomani, who was a well known scholar well versed in Islamic jurisprudence. The Act was a blessing for the Muslims.

Mr. Jinnah used his membership of legislature for the benefit of people in general and Muslims in particular. For example he proposed that the competitive examinations should be held in the sub continent. Indians should be appointed as officers in the defence forces, educational efforts must be vigorously pursed. Whenever necessary he cirticised the government but he never used unparliamentary language and fully maintained the dignity and decorum of the Parliament, a lesson that subsequent Parliamentarian would do well to learn.

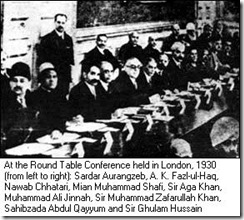

Rapid political changes took place after the failure of the Round Table Conference in London. Mr. Jinnah was disappointed with the tactics of the Congress party. When the Indians failed to agree on the future shape of things he was so disappointed that he decided to settle down in England and kept away from politics. But meanwhile the British Government promulgated the Government of Indian Act 1935. Politicians including Liaquat Ali Khan approached him and requested him to come to India because in a constitutional struggle he alone was suited to lead the Indian Muslims. A strong voice was that of Allama Iqbal. The poet was keeping an indifferent health and was to die soon but he fully trusted Jinnah’s talents. It was realised that Mr. Jinnah knew the British and the Congress like the palm of his hand. Since it was a constitutional struggle, the fate of the Mussalmans could be safely entrusted to him. He came back, took up the leadership of the Muslims League and turned into a mass organisation. It was no more a body of few elites, which met annually, passed a few resolutions and dispersed. The Muslim masses had now joined the organisation. They had conferred the title of Quaid-i-Azam (Great Leader) on Mr. Jinnah, who fully deserved it.

Rapid political changes took place after the failure of the Round Table Conference in London. Mr. Jinnah was disappointed with the tactics of the Congress party. When the Indians failed to agree on the future shape of things he was so disappointed that he decided to settle down in England and kept away from politics. But meanwhile the British Government promulgated the Government of Indian Act 1935. Politicians including Liaquat Ali Khan approached him and requested him to come to India because in a constitutional struggle he alone was suited to lead the Indian Muslims. A strong voice was that of Allama Iqbal. The poet was keeping an indifferent health and was to die soon but he fully trusted Jinnah’s talents. It was realised that Mr. Jinnah knew the British and the Congress like the palm of his hand. Since it was a constitutional struggle, the fate of the Mussalmans could be safely entrusted to him. He came back, took up the leadership of the Muslims League and turned into a mass organisation. It was no more a body of few elites, which met annually, passed a few resolutions and dispersed. The Muslim masses had now joined the organisation. They had conferred the title of Quaid-i-Azam (Great Leader) on Mr. Jinnah, who fully deserved it.

Elections were fought under the 1935 Act. The Quaid-i-Azam fully devoted his time to the organising and strengthening the Muslim League. The Parliamentary politics was a part of the main politics and assemblies had become important. The Quaid-i-Azam was a member of the Central Assembly, but was also guiding the League parties in Provincial assemblies. In the Centre the Quaid-i-Azam was the leader of the party and right hand man was Liaquat Ali Khan, who later became the Prime Minister of Pakistan.

In 1945 crucial elections were held in the sub-continent, in which the youth led by the All India Muslim Students Federation played a key role. Quaid-i-Azam was as usual chosen to represent the Bombay (Urban) constituency. I know personally that the Quaid-i-Azam at the time of his election was touring the far away North West Frontier Province. Raja Amir Ahmad Khan of Mahmudabad, as President of the All India Muslim Students Federation was supervising the elections. The Quaid-i-Azam was opposed by Hussain Bhai Lalji, as Ismaili, who was being backed by the Congress party. The Congress in a false statement had said that the Aga Khan had asked his community to vote for Hussain Bhai Lalji. But another prominent Ismaili leader Ibrahim Rahimtoola was very close to Quaid-i-Azam. Fortunately the Aga Khan happened to be in Delhi at that time. Rahimtoola immediately contacted him on phone. He not only denied having ever instructed the Ismailis to vote for Hussain Bhai but asked Rahimtoola to intimate all Ismaili families to vote for the Quaid-i-Azam. The members of the All India Muslim League at that time played a glorious role. A pamphlet stating the view of the Aga Khan solicting Ismailis to vote for the Quaid-i-Azam was printed and delivered overnight to all Ismaili families. Raja Saheb Mahmudabad told the writer that the pamphlet had the effect of the magic. The community already was pro-Jinnah and at sixes and sevens by Lalji’s dubious activities heaved a sigh of relief and voted for him.

‘League won 100% seats in the Central Assembly and about 70 to 90% in the Provincial Assemblies. Success at the hustings strengthened the Quaid-i-Azam’s hands and paved the way for Pakistan.

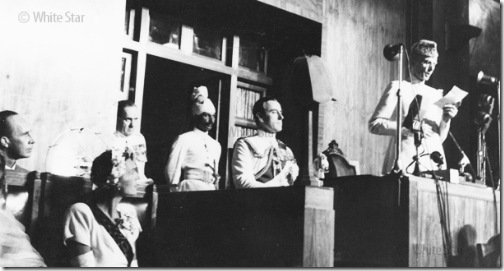

The Assembly after partition had the twin capacity of being the Constituent Assembly as well as the National Assembly. The Quaid-i-Azam was elected as its President besides being the Governor General. It was in this Assembly that the Quaid-i-Azam in his address on 11th August 1947 laid down the guidelines for future. In what Bolitho described as the “greatest speech of his life, the Quaid-i-Azam indicates that he wanted to see honesty, liberalism, clean life and noble society in Pakistan. It is sad – and also dangerous – to forget the direction that was prescribed by the Founder of Pakistan. But at the same time it must be admitted that it was in the National Parliament that guidelines for the future were laid by the Founder’.

The Quaid always kept his audience in mind, which enabled him to assess their mental caliber. When he appeared as a lawyer he knew the judges were usually men of experience and knowledge. He could therefore narrate the complex nuances and fine points of law. In Parliament too most of the members were aware of the problems of socio-political life. But in a public meeting of varied intellects and knowledge sat before him. Many points that he narrated were not easily understandable. So he spoke in a manner on things that were easily understood. For example in a meeting at Meerut he said:

“The fire is raging. I ring the bell. Bring the Firebrigade”. The point were went home at once and the people voicedly clapped. He had learnt Urdu and spoke to the masses in their language.

Jamiluddin Ahmad a former Professor of the Aligarh Muslim University who published his speeches, writer that “He did not claim to be saint or divine preaching to ordinary mortals. He did not foist his own views on his followers with dogmatic authority.” Speaking in Parliament with sophisticated audience was different and according to Jamiluddin from parliamentary speaker he rose to the heights of oratory.

On his voice and manners, He says: “His voice though lacking in volume but was rich in timbre. It was characterized by deep musical resonance…. The audience listened to him with bated breath……A motion of a finger, a little waving of the head, or a slight turning of his impressive figure would enthrall his audience. The incisive reasoning, the close analysis, the careful marshalling of facts and arguments, the laying of emphasis of points of vantage –all characteristic qualities of a lawyer –are also marked the Quaid-i-Azam’s way of speaking from the platform as well as the Parliament. He did not try to hoodwink the audience and kept far away from verbal jugglery and mental acrobatics. “Mr. Jinnah”, says the author, “distinguished himself as a brilliant and astute parliamentarian. In many a parliamentary battle he was the hero of the day….. During the first decade of the Legislative Assembly, established under the Government of Inida Act. 1919 he crossed swords with many powerful debaters and invariably came out with flying colours. His parliamentary speeches show masterly grasp of the subject under discussion and incisive reasoning whose appeal is irresistible. In the legislature, he had shone as the epitome of the Parliamentary decorum, the grand manner, the elegant style.”

I fully agree with Mr. Ahmad when he says:

For Parliamentary leadership he seems to be cut out from the beginning and Parliamentarian he always was. Quick perception of legal squabbles and legislative intricacies were ingrained in his blood.

Quaid-i-Azam Jinnah was not a tub-thumping politician. He did not even care to embellish his prose. Once he told his secretary to hurry up with his writing because his idea was to drive his point home than to waste time on artistic writing. He depended on facts, arguments and reasoning – characteristics that were an asset both in legal practice and Parliamentary debates.

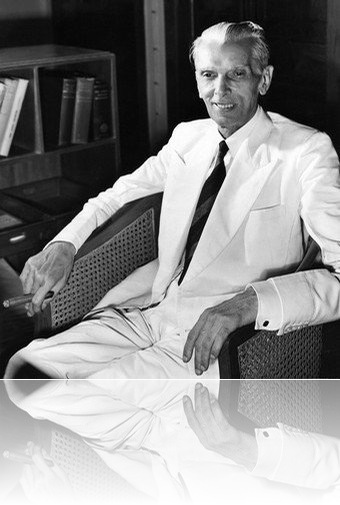

Quaid-i-Azam was a distinguished personality, very neat and clean and head and shoulders above the common run of men. His clothes – Western or Eastern – were always well pressed and well-stitched. I had the honour of seeing him at home, in the Parliament and on public platforms wearing three–piece suits, and black or white sherwanis. Even when old age had left deep marks on his face, his behaviour and deportment distinguished him. These were great qualities when he took the floor in the Parliament. Such characteristics are in history. Men like Quaid-i-Azam are rarer.

Short Bibliography

- Jinnah by Hector Bolitho (1954) John Murray, Alberndale Street London.

- Millat Ka Pasban Karam Haider (1983) Q.A. Academy, M.A. Jinnah Road, Karachi.

- Quaid-i-Azam Jinnah by Sharif al Mujahid (1981), Q.A. Academy, M.A. Jinnah Road, Karachi.

- Quaid-i-Azam and Education (1977) Board of Intermediate, Education, Karachi.

- Shahrah-e-Pakistan by Chowdhri Khaliquzzaman (1967) Anjum-e-Islamia Pakistan, Karachi.

- Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Founder of Pakistan Edited by Prof. Ziauddin, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Government of Pakistan.

- Q.A. Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Analysis of Parliamentary Attributes by Dr. Muhammad Umar, Al-Mahfooz Research Academy, Karachi.

- Speeches and Writings by Mr. Jinnah, Collected by Jamiluddin Ahmad (1942) published by Shaikh Mohammad Ashraf, Lahore.

- Jinnah of Pakistan by Stanley Wolpert, published by Oxford University Press, Karachi.

- Mohammad Ali Jinnah, A Political Study by M.H. Saiyed (1945) Sh. Mohammad Ashraf, Lahore.

Jinnah: The Man - The Young Jinnah

by Hector Bolitho

Jinnah Creator of Pakistan is the best biography of Jinnah yet written by a Westerner. Hector Bolitho is an English journalist. In this selection he considers some of the significant influences on the young Jinnah. Most of the Jinnah’s observers have noted that he was strict and methodical in his habits and attitudes. Both in small matters, such as his monocle, and in large matters, such as his belief in constitutional procedure, Jinnah remained consistent from his early teens to the end of his life. The picture Bolitho gives of the able young student and advocate, aware of his abilities and of the obstacles before him, is an important clue to Jinnah’s later activities.

In the heart of the bustling new city is old Karachi, the town of mellow houses that Jinnah knew as a boy. Some of the streets are so narrow, and the houses so low, that the camels ambling past can look in the first-floor windows. In one of these narrow streets, Newnham Road, is the house – since restored and ornamented with balconies – where Mohammad Ali Jinnah was born. The date is uncertain: in the register of his first school, in Karachi, the day is recorded as October 20, 1875; but Jinnah always said that he had been born on Christmas Day – in 1876. If the 1876 date is correct, he was seven days old when Queen Victoria was proclaimed the Kaiser-i-Hind, on the Plain of Delhi. He was born in the year that the Imperial India was created, and he lived to negotiate, with Queen Victoria’s great-grandson, for its partition and deliverance from British rule.

In one of the tenement houses in old Karachi there lives Fatima Bai, a hand some old woman, aged eighty six; one of the few persons who can remember Mohammad Ali Jinnah when he was a boy. She was a bride of sixteen, married to one of the Jinnah’s cousins, when she arrived in the family home in Karachi. The year was 1884. Jinnah was then seven years old.

Fatima Bai lives with her son, Mohammad Ali Ganji , in rooms at the top of a flight of bare stone stairs. I went there one evening and she received me in her own room, in which there were her bed, an immense rocking-chair, and a wardrobe where among the bundles of clothes, the few existing documents – the family archives – were kept. Mohammad Ali Ganji spread the papers on the bed, beside his mother, and then gave me the bones of the early story.

Although Jinnah’s immediate ancestors were Muslims – followers of the Khoja sect of the Aga Khan – they came, like so many Muslim families in India, of old Hindu stock. Mohammad Ali Ganji said that the family migrated to the Kathiawar Peninsula from the Multan area, north of the Sind desert, long ago. From Katiawar, they moved to Karachi, where they settled and prospered in a modest way.

When Jinnah was six years old, he was sent to school in Karachi. When he was ten, he went on a ship to Bombay, where he attended the Gokul das Tej Primary School, for one year. He was eleven when he returned to Karachi, to the Sind Madrasah High School; and he was fifteen when he went to the Christian Missionary Society High School also in Karachi.

Mohammed Ali Ganji said, “In the same year that he was at the Mission School, he was married by his parents as was the custom of the country, to Amai Bai, a Khoja girl from Kathiawar. In 1892 he went to England to study law and, while he was there, his young wife died. Soon afterwards, his mother died, and his father became very poor…”

Fatima Bai raised her hand and interrupted her son: she said, “He was a good boy; a clever boy. We lived, eight of us, in two rooms on the first floor of the house in Newnham Road. At night, when the children were sleeping, he would stand a sheet of cardboard against the oil lamp, to shield the eyes of the children from the light. Then he would read, and read. One night I went to him and said, ‘You will make yourself ill from so much study,’ and he answered, ‘Bai, you know I cannot achieve anything in life unless I work hard.’ “

As Fatima Bai finished her story, an old man appeared at the door; a smiling old Muslim with tousled, snow-white hair. His name was Nanji Jafar. He came in, sat in the rocking-chair and said that, as far as he knew, he was in his eighties. Though he had been at school with Jinnah, all he could recall was, “I played marbles with him in the street…” When I asked, “Can you remember anything he said to you?” he looked from beneath his thick brows and repeated, “I played marbles in the street with him.”

I asked him to close his eyes and to see, once more, the coloured glass marbles in the dust. Nanji Jafar closed his eyes and deeper into his memory: then he told his only anecdote of Jinnah’s boyhood. One morning, when Nanji Jafar was playing in the street, Jinnah, then aged about fourteen, came up to him and said, “Don’t play marbles in the dust; it spoils your clothes and dirties your hands. We must stand up and play cricket.”

The boys in Newnham Road were obedient: they gave up playing marbles and allowed Jinnah to lead them from the dusty street to a bright field where he brought his bat and stumps for them to use. When he sailed for England at the age of sixteen, he gave Nanji Jafar his bat and said, “You will go on teaching the boys to play cricket while I am away.”

All Jinnah’s story is in the boyhood dictum – “Stand up from the dust so that your clothes are unspoiled and your hands clean for the tasks that fall to them….

At the time when Jinnah finished his schooling, there was an Englishman, Frederick Leigh Croft, working as an exchange broker in Bombay and Karachi. He was heir to a baronetcy – a thirty-two-year-old bachelor, described by a kinswomen who remembers him as “something of a dandy, with a freshly picked carnation in his buttonhole each morning, a recluse and wit, uncomfortable in the presence of children, whom he did not like.” But he liked Mohammad Ali Jinnah, and was impressed by his talents. Frederick Leigh Croft ultimately persuaded Jinnah Poonja to send his son to London, to learn the practice of law.

Mohammad Ali Jinnah was not yet sixteen when he sailed across the Arabian Sea, towards the western world….which was to imbue him with an Englishness of manner and behaviour that endured to his death.

Mrs. Naidu wrote of Jinnah some years later, “It seems a pity that so fine an intelligence should have denied itself the hall-mark of a University education.” Jinnah appearantly withstood the temptations of literature, and art, and even of history. His mind seldom doted on the past, and it would seem that his habits in London were narrowed down – that his way was from lectures in Lincoln’s Inn, to debates in the House of Commons, without any pausing in the National Gallery on the way. He was to do two things brilliantly in his life: he was to become a great advocate, and he was to create a nation. From the beginning, he did not dissipate his energies with hobbies, nor his strength in dalliance. His chief passions were in his mind.

In an address to the Karachi Bar Association in 1947, Jinnah recalled, “I joined Lincoln’s Inn because there on the main entrance, the name of the Prophet was included in the list of great law-givers of the world.” He spoke of the Muhammad as “a great statesman, and a great sovereign.” His appreciation of the Prophet was realistic: perhaps his political conscience, as a Muslim, had already begun to stir while he was in England.

Jinnah told Dr. Ashraf that, during the last two years in London, his time was “utilized for future independent studies for the political career” he already “had in mind.” Jinnah also said, “Fortune smiled on me, and I happened to meet several important English Liberals with whose help I came to understand the doctrine of Liberalism. The Liberalism of Lord Morley was then in full sway. I grasped that Liberalism, which became part of my life and thrilled me very much.”

This awakening in politics coincided with significant personal changes. Up to April 1894, Mohammad Ali Jinnah used his boyhood name, Jinnahbhai – bhai being a suffix used in Gujrati language which was his mother tongue. On April 14, 1894, he adopted the English fashion in names and became Mr. Jinnah, the form he used for the rest of his life. He had also abandoned his “funny long yellow coat” and adopted English clothes; and – perhaps encouraged by the sight of Mr. Joseph Chamberlain in the House – he had bought his first monocle.

It must have been an important moment in the development of his courage, and his personality, when he went to an optician’s shop in London and bought the first of many monocles, which he wore during the next fifty year – even at the end, when he was being carried into his capital on a stretcher; a dying warrior, holding the circle of glass between his almost transparent fingers.

***********************

Jinnah had said that “the Liberalism of Lord Morley” thrilled him very much. The thrill much have been intensified on June 21, 1892, when he read of the Royal Assent to the Amendment to the Indian Councils Act, empowering the Viceroy to increase the numbers in the Legislative and Provincial Councils – an amendment that gave the people of India, for the first time, “a potential voice” in the government of their country.

The beginning of Jinnah’s partiality for Liberalism was well-timed. At the end of May 1892, Mr. Gladstone spoke “with a vigour and animation most remarkable in a man of eighty-two.” He was rewarded in the following August, when the Liberals came into power after six years of Tory rule under Lord Salisbury.

The early 1890’s offered refreshing opportunities for any young novice in politics, newly arrived from India, anxious to learn, and naturally in love with agitation and reform. In 1893, when Jinnah must have recovered from his loneliness and “settled down,” he was able to listen to some of the lively debates over Mr. Gladstone’s Irish Home Rule Bill: he was able also to study English reactions to affairs in India, and Egypt; to watch the growing power of Labour, and to develop his sympathy with the political emancipation of women – a reform that became a fixed part of his political creed when he returned to India.

There was another stiring innovation, nearer his own heart. Jinnah arrived in London in time to watch – perhaps to help – the election of the first Indian, Dadabhai Naoroji, to the British Parliament, as a member for the Central Finsbury.

Dadabhai Naoroji was a Parsee, aged sixty-seven at the time of his return: for many years he had been a businessman in London. Photographs of him, in later life, reveal some of the reasons why he came to be known as the “Grand Old Man of India.” His humorous old eyes, long white beard, and relaxed hands, proclaim the teacher, about whom young Indians gathered to learn – rather than the furious agitator in love with change for its own sake.

When Dadabhai Naoroji announced his intentions to stand as Liberal candidate for Central Finsbury, Lord Salisbury committed the clumsy foly, in a speech at Edinburgh, of saying, “I doubt if we have yet got to the point of view where a British constituency would elect a black man.” The Scottish electors shouted “Shame!....” Victoria, attended by Indian servants and engrossed in her study of Hindustani, was much displeased.

The unhappy insult – addeldy unfortunate because Dadabhai Naoroji had a paler skin that Lord Salisbury – soon made the Parsee Liberal into a hero. The chapters in his biography, describing the controversy awakened by the election in Finsbury, make an exciting story. Women’s Suffrage was one of his aims, and he was therefore overwhelmed by women helpers. Among the letters sent o him was one from Florence Nightingale: “I rejoice beyond measure,” she wrote “that you are now the only Liberal candidate for Central Finsbury.”

Dadabhai Naoroji was elected, with a majority of three, and the quick-tongued Cockneys who have voted for him turned his difficult name into “Mr. Narrow Majority.”

Mohammad Ali Jinnah was caught up in the excitement of the Finsbury election, and he prospered under the influence of Dadabhai Naoroji, whom he was to serve, as secretary, fourteen years later. It is reasonable to suppose that Jinnah learned much from Naoroji’s speeches; that he absorbed some ideas from the Grand Old Man….

Mohammad Ali Jinnah returned to India in the autumn of 1896. He was then a qualified barrister, aged almost twenty, and devoted to the Liberalism he had absorbed from Gladstone, Morley, and Dadabhai Naoroji. English had become his chief language, and it remained so, for he never mastered Urdu even he was leading the Muslim into freedom, he had to define the terms of their emancipation in an alien tongue. His clothes also remained English, until the last years of his life, when he adopted the sherwani and Shalwar of the Muslim gentlemen. And his manner of address was English: he had already assumed the habit, which he never gave up, of shaking his finger at his listener and saying, “My dear fellow, you do not understand.”

Mohammed Ali Jinnah sailed for Bombay in 1897, but he was to endure three more years of penury, and disappointment, before he began to climb. Mr. M.H. Saiyid, who was Jinnah’s secretary in later years, has written of this lean time. “The first three years were of great hardship and although he attended the office regularly every day, he wandered without a single brief. The long and crowded foot-paths of Bombay may, if they could only speak, bear testimony to a young pedestrian pacing them every morning from his new abode….a humble locality in the city, to this office in the Fort,….and every evening back again to his apartments after a weary, toilsome days spent in anxious expectation.”

As the turn of the century, Jinnah’s fortune changed, through the kindness of the acting Advocate-General of Bombey, John Molesworth MacPherson, who invited the young lawyer to work in his chambers. Mrs. Naidu wrote of this as “a courteous concession – the first of its kind ever extended to an Indian,” which Jinnah remembered as “a beacon of hope in the dark distress of his early struggles.”

***********************

The second advocate resumed his story: he said: “You must realize that Jinnah was a great pleader, although not equally gifted as a lawyer. He had to be briefed with care, but; once he had grasped the facts of a case, there was no one to touch him in legal argument. He was that God made him, not what he made himself, God made him a great pleader. He had a sixth sense: he could see around corners. That is where his talents lay. When you examine what he said, you realize that he was a very clear thinker, though he lacked the polish that a university education would have given him. But he drove his points home – points chosen with exquisite selection – slow delivery, word by word. It was all pure, cold logic.”

The first advocate then told another story. “One of the younger men practicing at that time - younger than Jinnah – was M.A. Somjee, who became a High Court Judge. They were appearing, as opposed counsel in a case which was suddenly called for on hearing. Mr. Somjee was another court at the time and the solicitor instructing him asked Jinnah to agree to a short adjournment. Jinnah refused. The solicitor then appealed to the judge, who saw no objection, provided Jinnah would agree. But Jinnah would not agree: he stood up and said: ‘My learned friend should have anticipated this and he should have asked me personally for an adjournment.”

“Jinnah’s arrogance would have destroyed a man of less will and talent. Some of us used to resent his insolent manner – his overbearing ways – and what seemed to be lack of kindness. But no one could deny his power of argument. When he stood up in Court, slowly looking towards the judge, placing his monocle in his eye – with the sense of timing you would expect from an actor – he became omnipotent. Yes, that is the word, omnipotent.”

“May be,” said the third advocate, “but, always, with Jinnah one comes back to his honesty. Once when a client was referred to him, the solicitor mentioned that the man had limited money with which to fight the suit. Nevertheless, Jinnah took it up. He lost – but he still had faith in the case and he said that it should be taken the Appeal Court. The solicitor again mentioned that his client had no money. Jinnah pressed him to defray certain of the appeal expenses out of his own pocket and promised to fight the case without any fee for himself. The time, he won; but when the solicitor offered him a fee, Jinnah refused – arguing that he had accepted the case on the condition that there was no fee.”

I’ll tell you another story along that line,” said the second advocate. There was a client who was so pleased with Jinnah’s services in a case, that he sent him an additional fee. Jinnah returned it, with a note, ‘This is the amount you paid me-. This was the fee. Here is the balance-.’ “

When the three lawyers were asked, “Did you merely admire Jinnah or did any of you become fond of him?” one of them answered, “Yes, I was genuinely fond of him, because of his sense of justice. And because, with all the differences and bitterness of political life. I believe he was a man without malice: hard, maybe, but without malice.

*********************

Two of the advocates who spoke Jinnah were Hindus: One was a Parsee. Some time later, a veteran Muslim barrister gave his different, perhaps more penetrating, impression of Jinnah’s work at the Bar. “One must realize,” he said, “that when he began to practice, he was the solitary Muslim barrister of the time: there may have been one or two others, but they did not amount to a row of pins. This was in a profession made up mostly of Hindus and Parsee. Perhaps they were over-critical of a Muslim – who came from business stock-setting up such a standard of industry. There was no pleasure in Jinnah’s life; there were no interests beyond his work. He laboured at his briefs, day and night. I can see him now; slim as a reed, always frowning, always in a hurry. There was never a whisper of gossip about his private habits. He was a hard-working, celibate, and not very gracious young man. Much too serious to attract friend. A figure like that invites criticism, especially in the lazy East, where we find it easier to forgive a man for his faults than for his virtues.”

*********************

During these years of Jinnah’s early success as a lawyer, he met Mrs. Sarojini Naidu, the first sophisticated, intelligent woman to observe his talents, to see beyond the arrogance of the young advocate. She wrote of him:

Never was there a nature whose outer qualities provided so complete an antithesis of its inner worth. Tall and stately, but thin to the point of emaciation, languid and luxurious of habit, Mohamed Ali Jinnah’s attenuated form is the deceptive sheath of a spirit of exceptional vitality and endurance. Somewhat formal and fastidious, a little aloof and imperious of manner, the calm hauteur of his accustomed reserve but masks – for those who know him – a naïve and eager humanity, an intuition quick and tender as a woman’s a humour gay and winning as a child’s. Preeminently rational and practical, discreet and dispassionate in his estimate and acceptance of life, the obvious sanity and serenity of his worldly wisdom effectually disguises a shy and splendid idealism which is the very essence of the man.

Mrs. Naidu’s warm regard for Jinnah was shared by many other young women who saw, as pride, what his lawyer friends called arrogance. Among them was an old Parsee lady, still living on Malabar Hill, who remembers Jinnah at the age of twenty-eight. She has said of him, “Oh, yes, he had charm. And he was so good looking. Mind you, I am sure he was aware of his charm: he knew his own strength. But when he came into a room, he would bother to pay a compliment – to say, ‘what a beautiful sari!’ Women will forgive pride, or even arrogance, in a man like that.”

Source: From Hector Bolitho, Jinnah Creator of Pakistan (London, 1954), pp. 3-5, 7-11, 14-5, 18-19, 21-22

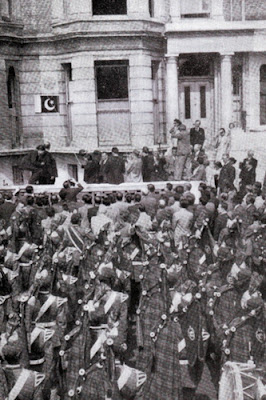

Jinnah House in London

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Credit: fiction~dreamer

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Credit: fiction~dreamer

Gandhi and Jinnah - a study in contrasts

An extract from the book that riled India's Bharatiya Janata Party and led to the expulsion of its author Jaswant Singh, one of the foun...

-

Speech on the Inauguration of the Pakistan Constituent Assembly on 14th August, 1947 Your Excellency, I thank His Majesty the King on behalf...

-

Reply to the Civic Address presented by the Quetta Municipality on I5th June, 1948. I thank you for your address of welcome and for the ki...