Quaid: A Study in Statesmanship

By Prof Sharif al Mujahid

Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah's claim to statesmanship lay in his two attributes: (i) his rational approach towards politics, and (ii) his keeping himself in close touch with the objective ground realities, however awkward, however complex, however shifting or confusing. Little surprising, he often made the right choice at the right moment.

Prescience, idealism, intellectual vigour, faith and resolution these qualities Jinnah had in an abundant measure. Qualities that having crystallized with the years had transformed him what he finally turned out to be in the last decade of his eventful life.

His sense of realism would never fail him, with this decisions stemming from a genuine pragmatic approach. An approach, which would always take the world as it was in its changing historic realities, only to have it improved to the extent that the existing possibilities permitted, with a view to upholding the ideals of freedom and the common good. Yet underlying all of Jinnah's politics were a specific set of moral values, reflecting the intellectual traditions and sociological norms among the historical realities of Indian Islam.

Jinnah, like Konred Adenauer of West Germany, was averse to following "a purely positively utilitarian policy of expediency". This is because he was not prepared to sacrifice moral principles and spiritual necessities for temporary political gains. Nor would he allow his realism to deflect him into a policy of opportunism. For his realism had a sound ethical base, his being a policy of conviction and of conscience all the time.

Nevertheless, his overwhelming sense of pragmatism shied him away, from the futile task of abstract theorizing and enabled him to concentrate all his energies on the practical mastery of the tangible, day-to-day, political problems and tasks.

Chance, and particularly the chance of genius, says Voltaire, "is an incalculable, factor in the story of the past". "Chance because it decides which people will survive", because it determines, what names will survive the ravages of time and tide. And that he should be able to rise to any occasion is perhaps the most significant mark of greatness in a statesman. Jinnah could do something more: he could crystallise a lifetime's faith into a single bold action. And such actions over a 30-year provide the key to his political career and success.

Barely twelve years after his debut into politics for instance, Jinnah brought the divided Hindu and Muslims on one platform, a "miracle" that had never happened again.

He also got this Hindu-Muslim unity consecrated in the famous (Congress-League) Lucknow Pact of 1916. For all that it meant, it was not the handwork of a mere politician. It was an act of faith: faith in Hindu-Muslim unity as the condition of Indian freedom. And it called for utmost tact, persuasive powers, and statesmanship of the highest order to breathe a spirit of compromise, of give-and-take, into the two warring parties, so mortally suspicious of each other.

Some ten years later, he devised an extremely viable formula for a Hindu-Muslim settlement. This was in the Delhi Muslim Proposals (1927). Despite Muslim reservations about joint electorates, he offered to waive the Muslim right to separate electorates, if certain basic Muslim demands were met. These demands were: Proportional representation for Muslims in the Punjab and Bengal, the separation of Sindh from Bombay Presidency the extension of reforms to the NWFP and Balochistan and one-third Muslim representation at the center. Within the united Indian framework, the Delhi Proposal ensured the setting up of five stable Muslim Provinces to match the six Hindu ones. Hence Maulana Abul Kalaam Azad hailing them as opening. "The door for the first time to the recognition of the real rights of Muslims in India". While negating the long-standing Hindu reservations on separate electorates, the Proposals guaranteed Muslims "a proper share in the future of India".

Initially, the Congress welcomed and accepted the Proposals, Later, however, it gave in to the Hindu Mahasabhaite pressure, and opposed the Muslim demands except for the one relating to the NWFP, and for a conditional acceptance of Sindh's separation.

This mean that Jinnah's spirit of accommodation was sadly supporting on the other side. He requested that "the Muslims should be made to feel that they are secured and safeguarded against any act of oppression of the majority" fell on deaf cars. So did his plea "to rise to that statesmanship which Sir Tej Bahadur describes". But for the rejection of his impassioned pleas, the subsequent history of India would have been different. Mere politicians, out to score tactical gains let slip through their fingers the chance of a lifetime. At this juncture, the only other political leader who could match Jinnah's breadth of vision and statesmanship was Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru.

In 1937 came another chance for a Hindu-Muslim rapprochement. From 1935 onwards, Jinnah had established an entente with the Congress at the center. In February 1935, he tried to negotiate an alternative to the Communal Award (1932) with Babu Rajendra Prasad, the Congress President. A viable formula was finally worked out, but the pressure built up by the Congress Nationalist Party under Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya, especially in Bengal and the Punjab, scuttled their efforts.

In the pre-1937 election period, despite Pandit Nehru's provocative denial of Muslim entity and identity in India's body politics on September 18, 1936, Jinnah had managed to keep him cool, offering the Congress an olive branch repeatedly. "Ours is not a hostile movement", he assured on August 20, 1936. He urged his Peshawar audience on October 19, "to unite to hammer out an advance nationalist bloc" from amongst themselves "to send to the Provincial Assembly". He exhorted Hindus and Muslims alike, at a public meeting at Nagpur's Chitnawis Park on January 1, 1937, to produce by a process of hammering fine steel and weed out those obstructing their march to freedom".

He declared on January 20, 1937 that "the urgent question facing every nationalist in India is how to create unity out of diversity and not of fight each other'.

With this end in view, he promoted the establishment of "something like a concordat" with the Congress during the 1937 elections, especially in the U.P. and Bombay. After the elections, he instructed the League Leaders to shun joining the interim ministries in these provinces. He instructed A.M.K. Dehalvi, Muslim League Assembly Party leader in Bombay, to reject out of hand Governor Brabourn's offer to head the interim ministry. Husseinally Rahimtulla and the Raja of Salempur were expelled for joining the Cooper and Chatter ministries in Bombay and the U.P. respectively.

Yet, when the Congress finally took office in July 1937, it by passed the Muslim League and Jinnah. It opted for Unitarianism a la the Nehru Report as against Muslim federalism, offered "absorption" instead of "partnership", and called for the dissolution of Muslim League parties in the legislatures for being considered for a share in power. The Congress justified the formation of exclusive one-party governments on the basis of the collective responsibility principle, but when it came to provinces such as the NWFP and Assam where it did not command an absolute majority, it flouted this principle and went in coalition ministries.

The failure of the Congress to exploit its spectacular electoral gains in 1937 for extending the areas of cooperation with the League is inexplicable unless explained in terms of it becoming "heady" with its unexpected victory and of a terrible lack of political prescience and foresight. For a plural society and for a multi-national country like India, Switzerland rather than England was the model coalition, rather than one-party government, the rule.

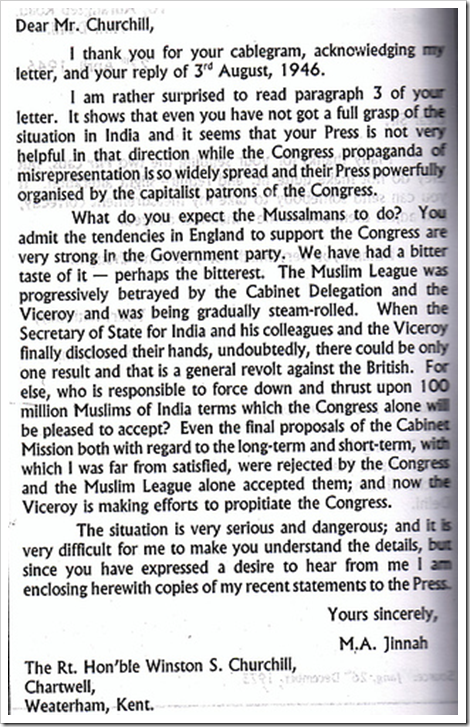

History shows that neglected opportunities do not, as a rule, return. However, Congress was presented the opportunity of reaching a peaceful settlement of the communal question in 1928, during 1930 (at the time of the Round Table Conference), during 1935-37 (Jinnah-Prasad Formula and the formation of provincial governments), and, finally, in 1946. But each time it failed, rather miserably. Of all these, the Cabinet Mission Plan (1946) presented the Congress leaders at this crossroad of history the chance of a lifetime, the chance perhaps of centuries. But none of them could rise to the occasion, because none of them had that "incredible clarity of vision", that "statecraft", and that "practical Bismarckian sense of the best possible" which, was Jinnah's alone, to quote the Aga Khan.

Bismarck, it is said, "was always emphatic that he could not make events". And if Jinnah had been asked about this situation at this juncture, he would have most probably said in the Bismarckian vein" "Politics are not a science based on logic; they are the capacity of always choosing at each instant, in constantly changing situations, the least harmful, the most useful". Again, like Bismarck, Jinnah, though perhaps taken by surprise by the Congress" reservations on the Cabinet Mission Plan, would turn the blunders of his enemies to his own advantage, to emerge victorious in the end.

But this anticipates. For the moment, it would suffice to note that Jinnah's crucial decision to accept the Cabinet Mission Plan demonstrated, perhaps more than anything else, this genius in statesmanship - a measure of statesmanship perhaps unmatched by the political giants involved in writing the last chapter of the British Raj in India. Hence the Aga Khans' verdict:

"In the one decision to accept the Cabinet Mission Plan, combining as it did sagacity, shrewdness, and unequalled political flair, he justified.... My claim that he was the most remarkable of all the great statesmen that I have known. In puts him on a level with Bismarck."

Remember, the Aga Khan was himself a statesman of a rare caliber, having occupied the president ship of the League of Nations.

Political genius, it is often said, lies in compromise. But this is only true within limits. An empirical approach is a distinguishing characteristic of a statesman, but that statesman alone is great who does not lose his purposive political creed in the exercise of power vested in him. The Muslim nation had, of course, authorized Jinnah to negotiate was operative only within the framework of the nation's cherished aspirations and supreme objective. The genius for compromise could never be carried beyond a recognizable point. The genius for compromise could never be carried beyond a recognizable point, the limit to compromise being set by the words of high purpose, such as Justice, Honour and Equity. In accepting the Mission Plan, Jinnah had compromised to the extent of suffering central control over the Muslim areas in respect of Defence, Foreign Affairs and Communications. But in attempting to erode the grouping provision on the one hand and envisaging and strenuously striving for a strong Centre on the other, the Congress had brazenly trespassed the limits to compromise. The Mission Plan, as formulated by its authors, ensured for Muslim Justice, Honour and Equity in the future Indian dispensation - though not in full, but in a substantial measure. The Plan, as the Congress had interpreted and proposed for implementation, had sought to cut across these high, non-compromisable principles. Jinnah had, therefore, to revoke his earlier acceptance of the Plan.

"The Future", says A.J.P. Taylor, a British historian, "is a land of which there are no maps; and historians err when they describe even the most purposeful statesman as though he were marching down a broad highroad with his objective already in sight. More flexible historians admit that a statesman has an alternative course before him; yet even they depict him as one choosing his route at crossroad. Certainly the development of history has its own logical laws. But these laws resemble rather those by which floodwater flows into hitherto unseen channels and forces itself finally to an unpredictable sea."

And if the Mission Plan had forced Indian politics through hitherto unseen channels on to an unpredictable sea, Jinnah, like Bismarck in such situations "proved himself master of the storm, a daring pilot in extremities. Like Bismarck again, even in the extremely difficult situation spawned by the British adverse verdict on the Pakistan demand, he never, even for a moment, let the initiative slip through his dexterous fingers.

Part of the wisdom of statecraft, to barrow a phrase from Richard Goodwin, is "to leave as many options open as possible and decide as little as possible... Since almost all-important judgments are speculative, you must avoid risking too much on the conviction that you are right. "The other half of the wisdom of statecraft is to "accept the chronic lubricity and obscurity of events without yielding, in Lincoln's words, firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right. Such acceptance rules out the contingency of keeping too many options open for too long, lest such keeping should paralyse the lobe of decision and end up in losing the game altogether. Thus, within the parameters of this framework, Jinnah's crucial decisions, first to accept the Mission Plan and later, when confronted with impossible congress conditions, to reject it, represent the two-halves of the wisdom of statecraft.

Jinnah's statecraft as well fulfils a test proffered by Bismarck himself: "Man cannot create the current of events. He can only float with it and steer." And the genius of Jinnah lay in his adroitly and successfully steering the adverse current of events during 1946 to bring the battered Muslim ship, safe and sound ashore within a year.

To sum up, then, Jinnah had a keep appreciation of the truth that politics is the art of the possible, that ends must conjoin and be conducive to means, that the best must be made of what is beyond one's power to change. Not only did he adroitly exploit to the full opportunities provided by his opponents. More importantly, like Mazzini, he also believed in creating opportunities through his own efforts. He had an iron will, and an unwilling faith in himself and his mission. To make these attributes the more impregnable and consequential, he was also resolute, fearless, courageous, calculating, and even somewhat reckless at time.

Yet he was farsighted, and, not withstanding the fierce invectives he had hurled oft and anon in the face of the "hated" congress, he always preferred the path of moderation and conciliation. Cautious for most part, he never took a step he could not retrace. The enabled him to stretch the hand of conciliation and compromise whenever such an opportunity presented itself. And it is a measure of the elasticity of his temper that the could change his political theosophy dewing his mid. Sixties, after over thirty years in public life, that he could accept the Mission Plan after pronouncing the "Pakistan-or- Perish" dictum, that he could call for "burying the hatchet" once the goal was achieved, that he could even preach friendship and collaboration with those to whom he was but lately so vehemently opposed. And, as in the case of Bismarck, his greatest, and perhaps most admirable, quality was to be content with limited success.

All told, it were these qualities that enabled him to surpass "possibly everyone else in India, in practical political intelligence" that earned him probably one of the highest tributes from a statesman whose stature and calibre were themselves universally recognized. In his Memoirs, the Aga Khan remarks:

Of all the statesmen that I have known in my life - Clamenceau, Lloyd George, Churchill, Curzon, Mussolini, Mahatma Gandhi - Jinnah is the most remarkable.

None of these men in my view outshone him in strength of character and in that almost uncanny combination of prescience and resolution, which is statecraft.

(The writer was founder-Director, Quaid-e-Azam Academy (1976-89), and authored "Jinnah: Studies in Interpretation (1981)", the only work to qualify for the president's Award for Best Books on Quaid-e-Azam)

The Governor General

Lord Mountbatten graciously felicitated Jinnah and read the message from his cousin, King George, welcoming Pakistan into the Commonwealth. Jinnah replied:

“Your Excellency, I thank His Majesty on behalf of the Pakistan Constituent Assembly and myself. I once more thank you and Lady Mountbatten for your kindness and good wishes. Yes, we are parting as friends…and I assure you that we shall not be wanting in friendly spirit with our neighbors and with all nations of the world.”

A witness reported:

“If Jinnah’s personality is cold and remote, it also has a magnetic quality -- the sense of leadership is almost overpowering…here indeed is Pakistan’s King Emperor, Archbishop of Canterbury, Speaker and Prime Minister concentrated into one formidable Quaid-i-Azam.”

The Plan of June 3, 1947

The existing Constituent Assembly would continue to function but any constitution framed by it could not apply to those parts of the country which were unwilling to accept it. The procedure outlined in the statement was designed to ascertain the wishes of such unwilling parts on the question whether their constitution was to be framed by the existing Constituent Assembly or by a new and separate Constituent Assembly. After this had been done, it would be possible to determine the authority or authorities to whom power should be transferred.

The Provincial Legislative Assemblies of Bengal and the Punjab (excluding the European members) will therefore each be asked to meet in two parts, one representing the Muslim majority districts and the other the rest of the Province.

The members of the two parts of each Legislative Assembly sitting separately will be empowered to vote whether or not the Province should be partitioned. If a simple majority of either part decides in favour of partition, division will take place and arrangements will be made accordingly.

For the immediate purpose of deciding on the issue of partition, the members of the Legislative Assemblies of Bengal and the Punjab will sit in two parts according to Muslim majority districts and non-Muslim majority districts. This is only a preliminary step of a purely temporary nature as it is evident that for the purposes of final partition of these Provinces a detailed investigation of boundary questions will be needed; and, as soon as a decision involving partition has been taken for either Province, a Boundary Commission will be set up by the Governor General, the membership and terms of reference of which will be settled in consultation with those concerned.

Moreover, it was stated that the Legislative Assembly of Sindh was similarly authorized to decide at a special meeting whether the province wished to participate in the existing Constituent Assembly or to join the new one. If the partition of the Punjab was decided , a referendum would be held in the North-West Frontier Province to ascertain which Constituent Assembly they wished to join. Baluchistan would also be given an opportunity to reconsider its position and the Governor General was examining how this could be most appropriately done.

In his broadcast, Mountbatten regretted that it had been impossible to obtain the agreement of Indian leaders either on the Cabinet Mission plan or any other plan that would have preserved the unity of India. But there could be no question of coercing any large area in which one community had a majority to live against their will under a government in which another community had a majority. The only alternative to coercion was partition.

On the morning of June 4, the Viceroy held a press conference and said for the first time publically that the transfer of power could take place on "about 15 August" 1947.

The Council of the All India Muslim League met in New Delhi on 9th and 10th of June 1947 and stated in its resolution that although it could not agree to the partition of Bengal and the Punjab to give its consent to such partition, it had to consider the plan for the transfer of power as a whole. It gave full authority to the Quaid-i-Azam to accept the fundamental principles of the plan as a compromise and left it to him to work out the details.

The All India Congress Committee passed a resolution on June 15 accepting the 3rd June plan. However, it expressed the hope that India would one day be reunited.

New Indian Policy and Mountbatten's Appointment as the Viceroy

His Majesty's Government desire to hand over their responsibility to authorities established by a Constitution approved by all parties in India in accordance with the Cabinet Mission's plan, but unfortunately there is at present no clear prospect that such a Constitution and such authorities will emerge. The present state of uncertainty is fraught with danger and cannot be indefinitely prolonged. His Majesty's Government wish to make it clear that it is their definite intention to take the necessary steps to effect the transference of power into responsible Indian hands by a date not later than June 1948…if it should appear that such a Constitution will not have been worked out by a fully representative Assembly before the time mentioned, His Majesty's Government will have to consider to whom the powers of the Central Government in British India should be handed over, on the due date, whether as a whole to some form of Central Government for British India or in some areas to the existing Provincial Governments, or in such other way seem most reasonable and in the best interests of the Indian people.

In regard to the Indian States, as was explicitly stated by the Cabinet Mission, His Majesty's Government do not intend to hand over their powers and obligation under paramountcy to any government of British India. It is not intended to bring paramountcy, as a system, to a conclusion earlier than the date of the final transfer of power, but it is contemplated that for the intervening period the relations of the Crown with individual States may be adjusted by agreement.

It was announced at the same time that Rear-Admiral the Visount Mountbatten would succeed Lord Wavell as the Viceroy in March. Lord and Lady Mountbatten landed at Delhi on March 22, 1947 and he took over as the Viceroy two days later. He could very well have represented to the British Government that both the Congress and the Muslim League had already asked for the partition of India into Muslim-majority and non-Muslim majority areas and sought their permission to embark upon the process of partition straightaway. But he chose to follow the policy that first the attempt to transfer power in accordance with the Cabinet Mission plan must continue. It is to that end, therefore, that he first directed his endeavors.

Mountbatten's relations with the Congress party had a flying start. The foundation of Nehru's friendship with Lord and Lady Mountbatten had been laid in March 1946 when the Indian leader visited Singapore. The political conditions in India too had changed in favor of the Congress. In post-independence India the Congress party was expected to rule the country. Consequently, it was the Congress's friendship that had now to be cultivated. The fact that Mountbatten personally was bitterly opposed to partition, made it much easier for him to court the Congress leaders.

Mountbatten's relations with the Congress party had a flying start. The foundation of Nehru's friendship with Lord and Lady Mountbatten had been laid in March 1946 when the Indian leader visited Singapore. The political conditions in India too had changed in favor of the Congress. In post-independence India the Congress party was expected to rule the country. Consequently, it was the Congress's friendship that had now to be cultivated. The fact that Mountbatten personally was bitterly opposed to partition, made it much easier for him to court the Congress leaders.All these factors greatly increased the already formidable odds facing the Quaid-i-Azam in his fight for Pakistan. In his meetings with Mountbatten, he refused to budge from the position that Pakistan was the only solution acceptable to the Muslim League.

The Interim Government (1946)

The Working Committee of the Muslim League had decided in the meantime that Friday 16 August, 1946 would be marked as the 'Direct Action Day".There was serious trouble in Calcutta and some rioting in Sylhet on that day. The casualty figures in Calcutta during the period of 16-19 August were 4,000 dead and 10,000 injured. In his letter to Pethick-Lawrence, Wavell had reported that appreciably more Muslims than Hindus had been killed. The "Great Calcutta Killing" marked the start of the bloodiest phase of the "war of succession" between the Hindus and the Muslims and it became increasingly difficult for the British to retain control. Now, they had to cope with the Congress civil disobedience movement as well as furious Muslims that had also come out in the streets in thousands.

The negotiations with the League reached a deadlock and the Viceroy decided to form an interim government with the Congress alone, leaving the door open for the League to come in later. A communiqué was issued on August 24 which announced that the existing members of the Governor General's Executive Council had resigned and that on their places new persons had been appointed. It was stated that the interim government would be installed on September 2.

Jinnah declared two days later that the Viceroy had struck a severe blow to Indian Muslims and had added insult to injury by nominating three Muslims who did not command the confidence of Muslims of India. He reiterated that the only solution to Indian problem was the division of India into Pakistan and Hindustan. The formation of an interim government consisting only of the Congress nominees added further fuel to the communal fire. The Muslims regarded the formation of the interim government as an unconditional surrender of power to the Hindus, and feared that the Governor General would be unable to prevent the Hindus from using their newly acquired power of suppressing Muslims all over India.

After the Congress had taken the reins at the Center on September 2, Jinnah faced a desperate situation. The armed forces were predominantly Hindu and Sikh and the Indian members of the other services were also predominantly Hindu. The British were preparing to concede independence to India if they withdrew the Congress was to be in undisputed control, the Congress was to be free to deal with the Muslims as it wished. Wavell too, felt unhappy at the purely Congress interim government. He genuinely desired a Hindu-Muslim settlement and united India, and had worked hard for that end.

Wavell pleaded with Nehru and Gandhi, in separate interviews, that it would help him to persuade Jinnah to cooperate if they could give him an assurance that the Congress would not insist on nominating a Nationalist Muslim. Both of them refused to give way on that issue.Wavell informed Jinnah two days later that he had not succeeded in persuading the Congress leaders to make a gesture by not appointing a Nationalist Muslim. Jinnah realized that the Congress would not give up the right to nominate a Nationalist Muslim and that he would have to accept the position if he did not wish to leave the interim government solely in the hands of the Congress. On October 13, he wrote to Wavell that, though the Muslim League did not agree with much that had happened, "in the interests of the Muslims and other communities it will be fatal to leave the entire field of administration of the Central Government in the hands of the Congress". The League had therefore decided to nominate five members for the interim government. On October 15, he gave the Viceroy the following five names:

Liaquat Ali Khan, I.I Chundrigar, Abdur Rab Nishtar, Ghazanfar Ali Khan and Jogindar Nath Mandal. The last name was a Scheduled Caste Hindu and was obviously a tit-for-tat for the Congress insistence upon including a Nationalist Muslim in its own quota.

- External Affairs and Commonwealth Relations: Jawaharlal Nehru

- Defence: Baldev Singh

- Home (including Information and Broadcasting): Vallahbhai Patel

- Finance: Liaquat Ali Khan

- Posts and Air: Abdur Rab Nishtar

- Food and Agriculture: Rajendra Parsad

- Labor: Ragjivan Ram

- Transport and Railways: M.Asaf Ali

- Industries and Supplies: John Matthai

- Education and Arts: C. Rajgopalacharia

- Works, Mines and Power: C.H. Babha

- Commerce: I.I. Chundrigar

- Law: Jogindar Nath Mandal

- Health: Ghazanfar Ali Khan

The Cabinet Mission (1946)

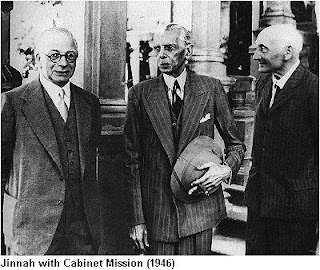

Cripps told the press conference on landing at Karachi on March 23 that the purpose of the mission was "to get machinery set up for framing the constitutional structure in which the Indians will have full control of their destiny and the formation of a new interim government." The Mission arrived in Delhi on March 24 and left on June 29.

Jinnah faced extreme difficulties in the three-month-long grueling negotiations with the Cabinet Mission. The first of these was the continued delicate state of his health. At a critical stage of the negotiations, he went down with bronchitis and ran temperature for ten days. But he never gave up the fight and battled till the end of the negotiations.

Secondly, the Congress was still much stronger than the Muslim League as a party. "They have the best organized -- in fact the only well organized -- political machine; and they command almost unlimited financial support…they can always raise mob passion and mob support…and could undoubtedly bring about a very serious revolt against British rule."-- Mountbatten's "Report on the Last Viceroyalty".

Thirdly, The Congress had several powerful spokesmen, while for the League Jinnah had to carry the entire burden of advocacy single-handedly.

Fourthly, the Mission was biased heavily in favor of the Congress. Secretary of State Pethick-Lawrence and Cripps, the sharpest brains among them, made no secret of their personal friendship for the Congress leaders.

Wavell was much perturbed by Pethick-Lawrence's and Cripps's private contacts with the Congress leaders and the deference they showed to Gandhi.

Finally, Jinnah suffered from the disadvantage that it was the Muslim League, a minority party, which alone demanded Pakistan. The Congress, the smaller minorities and the British Government including the comparatively fair-minded Wavell with whom the final decision lay, were all strongly opposed to the partition of British India.

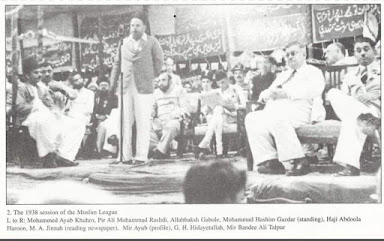

Quaid-i-Azam the constitutionalist took appropriate steps to strengthen his hand as the spokesman of the Muslim League. He convened a meeting of the Muslim League Working Committee at Delhi (4-6 April 1946) which passed a resolution that "the President alone should meet the Cabinet Delegation and the Viceroy. This was immediately followed by an All India Muslim Legislator's Convention. Nearly 500 members of the Provincial and Central Legislatures who had recently been elected on the Muslim League ticket from all parts of India attended it. It was the first gathering of its kind in the history of Indian politics and was called by some "the Muslim Constituent Assembly". In his presidential address, Jinnah said that the Convention would lay down "once and for all in equivocal terms what we stand for".

A resolution passed unanimously by the Convention (the "Delhi Resolution") stated that no formula devised by the British Government for transferring power to the peoples of India would be acceptable to the Muslim nations unless it conformed to the following principles:

That the zones comprising Bengal and Assam in the North-East and the Punjab, North-West Frontier Province, Sind and Baluchistan in the North-West of India, namely Pakistan, zones where the Muslims are in a dominant majority, be constituted into a sovereign independent State and that an unequivocal undertaking be given to implement the establishment of Pakistan without delay.

The two separate constitution-making bodies be set up by the people of Pakistan and Hindustan for the purpose of framing their respective Constitutions.

That the acceptance of the Muslim League demand of Pakistan and its implementation without delay are the sine qua non for Muslim League cooperation and participation in the formation of an Interim Government at the Center.

That any attempt to impose a Constitution on a united-India basis or to force any interim arrangement at the Center contrary to the Muslim League demand will leave the Muslims no alternative but to resist any such imposition by all possible means for their survival and national existence.

This impressive show of strength, staged in the very city where the members of the Cabinet Mission were quartered, demonstrated to the Mission and to all the others that the 100 million Muslims of India were solidly behind the demand for Pakistan and further that the Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah was their undisputed supreme leader.

The Mission began their talks by first informing themselves of the views of the different leaders and parties. When they found the view-points of the League and the Congress irreconcilable, they gave a chance to the parties to come to an agreement between themselves. This included a Conference at Simla (5-12 May), popularly known as the Second Simla Conference, to which the Congress and the League were each asked to nominate four delegates for discussions with one another as well as with the Mission. When it became clear that the parties would not be able to reach a concord, the Mission on May 16, 1946, put forward their own proposals in the form of a Statement.

Azad, the president of the Congress, conferred with the Mission on April 3 and stated that the picture that the Congress had of the form of government in future was that of a Federal Government with fully autonomous provinces with residuary powers vested in the units. Gandhi met the Mission later on the same day. He called Jinnah's Pakistan "a sin" which he, Gandhi, would not commit.

At the outset of his interview with the Mission on April 4 the Quaid was asked to give his reason why he thought Pakistan a must for the future of India.He replied that never in long history these was "any Government of India in the sense of a single government". He went on to explain the irreconcilable social and cultural differences between the Hindus and the Muslims and argued, "You cannot make a nation unless there are essential uniting forces. How are you to put 100 million Muslims together with 250 million people whose way of life is so different? No government can ever work on such a basis and if this is forced upon India it must lead us on to disaster."

The Second Simla Conference having failed to produce an agreed solution, on May 16, the Mission issued it's own statement.

The Cabinet Mission broadcast its plan worldwide from New Delhi on Thursday night, May 16, 1946. It was a last hope for a single Indian union to emerge peacefully in the wake of the British raj. The statement reviewed the "fully independent sovereign state of Pakistan" option, rejecting it for various reasons, among which were that it "would not solve the communal minority problem" but only raise more such problems. The basic form of the constitution recommended was a three-tier scheme with a minimal central union at the top for only foreign affairs, defense and communication, and Provinces at the bottom, which "should be free to form Groups with executive and legislatures," with each group being empowered to "determine the Provincial subjects to be taken in common". After ten years any Province could, by simple majority vote, "call for a reconsideration of the terms of the constitution". Details of the new constitution were to be worked out by an assembly representing "as broad based and accurate" a cross section of the population of India as possible. An elaborate method of assuring representation of all the communities in power structure was outlined with due consideration given to the representation of states as well as provinces.

The Quaid replied on the 19th , asking the Viceroy if the proposals were final or whether they were subject to change or modification, and he also sought some other clarification. The Viceroy promptly furnished the necessary explanations. It seemed as if the Quaid would accept the Viceroy's proposals. The Congress Working Committee met in Delhi on June 25 and by a resolution rejected the proposals, as "Congressmen can never give up the national character of the Congress or accept an artificial and unjust party, or agree to the veto of a communal group." Azad sent a copy of the resolution to the Viceroy and in his covering letter protested against the non-inclusion of a Muslim-Congressman from the Congress quota.

After the Congress stand had become known, the Working Committee of the Muslim League resolved to join the Interim Government, in accordance with the statement of the Viceroy dated 16th June. The interpretation of the Quaid-i-Azam was that if the Congress rejected the proposals, the League accepted them, or vice versa,the Viceroy would go ahead and form the interim Government without including the representatives of the party that decided to stand out. But the interpretation of the Viceroy and the Cabinet Mission was different from that of the Quaid-i-Azam.

It became clear that the protracted negotiations carried out for about three months by the Cabinet Mission did not materialize in a League-Congress understanding, or in the formation of an interim Government. Towards the end of June, the Cabinet Mission left for England, their task unfulfilled.

It had, however not been a complete failure. It was clear to the Indians that the acceptance of the demand for Pakistan would be an integral part of any future settlement of the Indian problem. In the meantime the League and the Congress were getting ready for elections to the Constituent Assembly.

Nations are born in the hearts of poets!!!

The poetry of Allama Iqbal was a breath of fresh air throughout Pakistan Movement... ...This is the historical and extremely memorable pic o...

-

Quaid-e-Azam addressing a group of students 1. My young friends, I look forward to you as the real makers of Pakistan, do not be exploit...

-

In 1913 the Quaid-i-Azam joined the All India Muslim League without abandoning the membership of the Congress of which he had been an active...